From poor village lad to legendary crime fighter

Tarrence Tan

He grew up poor in a remote village in Kelantan, but through sheer determination that was born out of obedience to his elders, Mohd Zaman Khan excelled in his studies and then, at the suggestion of a good friend, decided to join the police force.

It turned out to be a decision well made. From then on, he never looked back. Soon enough, while serving as the OCPD of Petaling Jaya, he began to develop a reputation as an effective crime buster. This reputation was cemented by sensational achievements during the time he served as Selangor CID chief and later as CPO in various states.

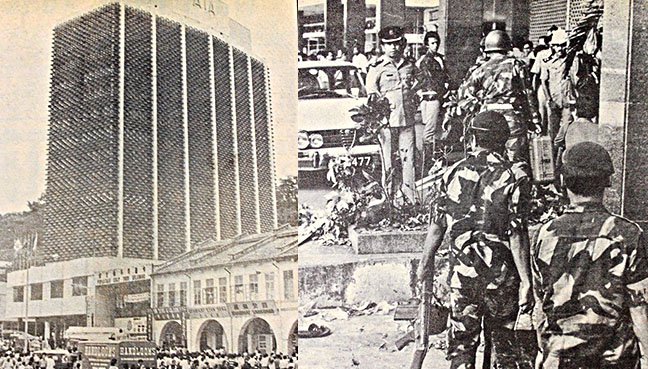

He was involved in many high profile cases, such as the the hunt for infamous criminals like Botak Chin and Bentong Kali and the successful handling of the 1975 hostage crisis at the AIA building in Kuala Lumpur.

AIA Building

Later on, he became the Director of Internal Security and then the Director-General of the Prisons Department, from which position he retired in 1997.

After decades of serving the country, Zaman, who is of Malay and Pashtun descent, is now making up for lost time with his family.

The man displays great patience with journalists who can't get enough of hearing about his adventures.

Below are extracts from an interview that FMT recently had with him.

Q: You are well known as a career police officer, but few know about your childhood. Could you share with us some of your early memories?

A: I was born in 1938 in Serendah, a small and remote village in Kelantan. We were very poor. My father spoke very little Malay, but he still saw it fit to send me and my elder brother to study in a Malay school near Pekan Uban, Kelantan.

I thank God that that my parents and uncles ensured that we obtained an education. They even built a small hut for us to study in.

In 1953, I was accepted into a school in Kota Baru after passing an entrance test which my father took me to.

We were fortunate to have dedicated teachers. I guess it's because they were from Penang and they noted the backwardness of the East Coast. I and my elder brother lived in a hostel and we were lucky that our teachers still supervised us after school hours, making sure that we studied.

Later on, I did very well in Form 6, when I was transferred to the Victoria Institution in Kuala Lumpur. I obtained distinctions in all four subjects.

Q: What inspired you to join the police force?

A: I had nowhere to go. My parents were poor and they needed me to work. I was unemployed for three months after I left school. My good friend, Abdul Rahim Abdul Rahman (who later set up Rahim & Co) suggested that he and I join the police as cadets. So that's when we went to apply at the police district office in Pasir Mas.

When we got there, a very nice OCPD, Tan Bian Guan, got a shock when he saw the results of my Form 6 exam. He said: "Why are you so stupid? I've been here for 15 years and I'm still in the same position. You had better go to university."

But we got the job anyway.

Q: One of the most interesting cases in which you were involved was the 1975 hostage crisis at the AIA building. What do you remember about it?

A: On Aug 4, 1975, I went to see the then IGP, Mohammed Hanif Omar, to thank him for promoting me to the position of Selangor CID chief. I was preparing to go home from Hanif s office when one of my boys came up to me and said that the Japanese Red Army (JRA) had taken over the AIA building. I said to him "F*** you, lah. You're trying to pull my leg."

But the young cadet said, "No, Sir. The Japanese have taken over the building." So there and then I became involved. We went there with the Special Action Unit (UTK), which was trained to neutralise kidnappers. And then we asked for more backup. Subsequently, we secured the area.

Then, two shots were fired and a letter was thrown from the building. The JRA wanted to negotiate for the release of their five comrades who were detained in Japan.

Ghazali Shafie, who was then Foreign Minister, came by to lend his negotiation skills. He also negotiated with the Japanese government, which eventually agreed to release the prisoners. But one prisoner refused to come out. The rest came to Malaysia but they never got out of the aircraft, which was parked at the Subang International Airport.

The JRA hostage takers were very sneaky. They didn't want to hand over the last hostage to us. But I was firm. I said, "No, you have to hand over all the hostages to us." I think they were trying to make sure that they would be allowed to fly out of Malaysia.

Ghazali was a true diplomat. He negotiated with several countries to allow the plane to go through. India and Sri Lanka initially refused to be involved. I heard him speaking on the phone. The Indian authorities said that if the plane doors were open, the authorities would shoot them. But Ghazali was persistent. Finally, the Indian authorities agreed to allow the JRA to refuel at their airport.

Initially, the Libyan government too didn't want to assist because it didn't want to be seen as collaborating with terrorists. But Ghazali kept on trying. He appealed to the Libyan Foreign Minister, talking to him like a brother. After some time, Libya agreed to help on humanitarian grounds.

Q: The current public perception of the police force is not very good. Some link it to corruption. Do you think corruption is linked to low police wages?

A: Well, the price of everything has gone up today. When I was young and I took my wife to Ipoh, I couldn't finish RM10.

Back then, kangkung was 10 cents. Today, it's a rich man's vegetable.

If I was in the government, I would focus on housing first. I would provide houses to government servants so they don t have to extort money from people.

Also, it's about the upbringing of people. We must teach the people about right and wrong when they are still children.

We still have a long way to go in fighting corruption, but we have to start somewhere.

The V.I. Web Page

The V.I. Web Page