REMEMBERING SCOUTING

IN 1951-1957

Ooi Boon Teck (V.I. 1951-1957)

|

Ooi Boon Teck was with the Wolf Pack at the Pasar Road English School before joining the V.I. At the V.I. he became a Scout in the 1st K.L. Troop. His other school activities included serving as president of the Literary and Debating Society, Editor of the Victorian and School Prefect. He was Treacher Scholar in 1954 and Rodger Scholar in 1955. In 1956-57, he was Assistant Scoutmaster, the year before he left V.I. for undergraduate studies. On graduation, he taught electrical engineering at the Technical College (Maktab Teknik), Kuala Lumpur. Then he pursued postgraduate studies. Boon Teck received the B.Eng. (Honours, first class) from the University of Adelaide (Australia), the S.M. from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (USA) and Ph.D. from McGill University (Canada), all in Electrical Engineering. He remained with McGill University, where he rose from Assistant Professor to Associate Professor and then to Professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. Two of his research interests have applications in Malaysia. One is on Linear Induction Motors, the motors which drive the Putra LRT in K.L. The second is on Direct Current Transmission, which connects the electric power system of Malaysia to Thailand. His invention of a new generation of such Direct Current Transmission System is licensed by a major multinational manufacturer and installations are in service in Sweden, Denmark, Australia and USA. In his recollections of his V.I. scouting days, written with insight, detail and self-deprecating humour, we have an invaluable record of an institution of the V.I. whose memories are held so dear by thousands of Victorians.

Before Merdeka

But if we felt bodily uncomfortable, our minds were no less ill at ease. We never seemed to be able to get things right. The stockings kept sliding down to our ankles, however much we tightened our garters. The six-inch scout knives, purportedly of stainless steel, turned rusty although we greased them again and again. However often we pressed down the waves on the ironing board, the brim of the scout hat regained their floppy undulations. Nobody told us that if we wanted the stiff, straight brims of the Royal Mounted Police, we would have to pay a price which would be beyond our means. Affordability was a consideration in the less prosperous Malaya of our days. If a boy were asked why he was not a Boy Scout, he would say that his parents considered Scouting a waste of time. But if the truth were known, the cost of uniform and incidental expenses in participating in scouting activities were not within his family budget. High visibility evoked comments. One was in the form of a doggerel, which I make a rough English translation here without attempting to match the Cantonese rhymes: Carries a big pole; Eats a bowl of rice; Falls asleep." Its standard of inaneness was comparable to a British example: A lazy lot of louts. They have their mothers' broom sticks, And their shirts are hanging out." I could sense other comments but they were never expressed openly. To appreciate the context, one must remember that my V.I. days belonged to the Emergency years. I left school a few months before our first Merdeka Day. Some of the feelings ran as follows: "One can understand your going to an English school as it is a way to assure a rice-bowl for life. But why volunteer to dress in the livery of a footman of the British?" To give an example that such a charge was not groundless, our Boy Scout Troop was placed "on duty" outside St. Mary's Church, next to the Padang, at the funeral service of the British High Commissioner, Sir Henry Gurney, after his convoy was ambushed at Fraser s Hill and he was assassinated. In today's world, we were there to provide the "friendly native" backdrop for CNN newsmen. I, myself, had wrestled with the Scout Promise, "On my honour, I promise.... to do my duty to God, the King and the Ruler of the State." To be fair, not everything was not lock, stock and barrel because "the Ruler of the State" was tagged in. When Princess Elizabeth hurried home from Kenya to ascend the throne after George VI died, "King" was changed to "Queen". To absolve oneself of the commitment, one could argue that a "promise" did not have the same binding power of an oath made with the shedding of the blood of a cockerel, as in a secret triad ceremony. Other calls for comments came from our Scout culture. We took pride in our brotherhood which has some of the customs and quaintness of a secret society. But whereas secret societies kept their oddities under cover, ours were on public display. The three-finger salute was a staple for comic skits. I remember one teacher saying in mockery, "Take my left hand, our left handshake brings us closer because both our hearts are on our left side." We did not help our image when in rallies with other youth groups, we burst into "yells": "Chikalaka, Chikalaka, chow, chow, chow, bomalaka, bomalaka, bow, wow, wow,... " The non-Scouts just shook their heads. In a way not considered to be obtrusive, for a long time, I used the Scout way of lacing my shoes. I remember one good comment though. I was in Standard Seven (Form 3, 9th year of schooling) and I was attending afternoon Chinese class (before switching to Latin, knowing that I would not pass Chinese in the Cambridge Syndicate Examination). The teacher was looking out of the doors in the direction of Birch Road, when he saw a couple of 2nd K.L. Scouts walking by. "You see the Scouts there." he said to the class, "They learn a lot of good things in Scouting." Hearing this from a Chinese teacher was truly unexpected. I was in the Scout Movement from the very beginning: as Wolf Cub in Pasar Road School; then Boy Scout, Senior Scout and Assistant Scoutmaster throughout my V.I. days. Thus the troubles which I described above arose because of my growing sensitivity to the world of politics. But I never wavered in my devotion to Scouting ideals. As they say, "Once a Scout, always a Scout." It was a pity that my Scouting experience was spoilt by the tinge of colonialism. After the era of colonialism, Scouting can be placed in its true footing. Together with Association football (soccer), badminton, rugby, and other sporting activities, Scouting is another contribution of the British people to the world. The Badge System I chuckled the first time I saw photographs of Soviet generals parading in Red Square. Some of them were octogenarians, but all of them were bedecked with military medals, which were so extensively and densely packed on their chests, that the cross-hair of a telescopic-rifle would search in vain for a penetrable spot and the sniper-assassin would not be able to collect his bounty. I was amused because it reminded me of our scouting days when we dreamt of the sleeves of our uniforms similarly bedecked with merit badges. Before he founded the Boy Scout Movement, Baden-Powell was recognized as the hero in the defense of Mafeking, in South Africa. If he knew how to sustain the morale of the defenders of Mafeking for many months against the besieging Boers, he had more than enough psychological acumen to motivate the young: whether they were pre-teens as Wolf Cubs, twelve to fifteen year-olds as Boy Scouts, fifteen to eighteen year-olds as Senior Scouts and young adults as Rovers. With insights into our acquisitiveness and natural instincts to show-off, we were led to develop our capabilities by collecting Tenderfoot, Second Class, and First Class Badges. In the Boy Scout age group, the prize was the Green Cord, which was worn around the shoulder. We looked forward to the day when we could swagger like a Police Inspector, who wore something similar. The highest goal of Senior Scouts was to become King Scout. In order to qualify, we had to collect badges for First Aid, Cooking, Backwoodsmanship, etc. Nowadays, there are many who consider that "learning" should be done for its own sake. They say that incentive systems such as badge collecting lead to personality disorders, in the forms of insatiable desires for degrees, titles and honours. But most healthy minds readily recognize the badge system for what Siddhartha Gautama regarded as "vessels" or "rafts" to cross from one shore to another shore in the sea of life. Upon successful crossing, one stops carrying the "raft" around. Looking back with some maturity, we cherish the badge system for what they were: "expedients" which helped us to grow vigorously during our schooldays. We grew in strength as we partook in all the "cliches" of Scouting life: ropes, knots, First Aid, semaphore, hiking, camping, camp fires. The truism was that knowing how to tie the reef knot, the bowline and the sheet-bend, for example, became less important when compared to new worlds which opened up through being actively engaged in the activities. In my case, there was self-discovery. I found out that I could tie the Scout knots just by looking at the diagrams. (No doubt, thousands of fellow scouts, who grow up to be engineers, have this ability.) Moving from knots to rope suspension bridges, I had the chance to study how the mangrove posts were lashed together into supporting frames which carried the main rope of the bridge, the same rope used in the tug-of-war event on sports day. Such exposure, in no small way, helped me choose my career as an engineer. In the cultural scene, ropes and knots led me to take an interest in pre-industrial civilizations (before the invention of nails, bolts and screws and zips, when ropes were the means of attachment and fastening). At our young age, we just wished that we could throw a lasso as in the cowboy movies. One or two scouts practised and practised until they could twirl a lariat centered around themselves. I kept a First-Aid Kit, complete with a roll of lint, cotton wool for dressing, tincture benzol for antiseptic and a large triangle piece of linen to be used as an arm sling. The arm sling seemed to be the center-piece in First-Aid training and we practised setting an arm in sling with whomever we could persuade to lend his arm. I think that it was "Skipper" (Geoffrey Geldard) who teased us that we were only good for compounding a simple fracture. We laughed it off as a good joke. If someone had told us that in the First Aid involved pain and suffering and one had to be ever so gentle, the lesson did not sink in. The moment of truth came on one Annual Sports Day, when a competitor fell and broke his collar bone. There I was, with a golden opportunity to do the Good Turn of the Day by giving him First Aid. I wanted to put the sling on him. The ingrate kept turning down all my overtures. He was hurting and my shuffling around hurt him all the more. Finally, someone came with a car to take him to hospital. I tried to help him into the car, but holding on to him caused him more pain. I was not happy that he was not cooperative and compliant. It took me a while to realize that he would hate the sight of the Scout uniform from that day on and it was all due to my fault. To fail is also to learn. But the lessons would have been better learned and quicker too, if it were I, who suffered the pain. The fact of the matter is that First Aid care required a higher degree of training and practice than we could ever be given. In litigation-mad North America, the Do-Gooder s first course of action is to desist: to restrain his instincts to lend his hand. The second step is to call the ambulance and wait for the arrival of certified para-medics. We received strong family support in all the things we did as children. Grandmother worked the foot-pedal of her Singer sewing machine to piece together cloth in the Oxbridge blues of the school colours, which fitted to two wooden batons, became our semaphore flags. The flags fluttered and snapped in the air as our arms spelled out symbolic representations of the Roman alphabet. We never got a key-and-buzzer in Morse code signaling. Our mouths would go, "Di, dah, di, di...", to vocalize the dots and dashes. Unknowingly, we were initiated to binary codes. I had to wait many years to my undergraduate course on Boolean algebra, to renew acquaintance, to learn that the same dots and dashes (0 and 1) are the medium of computer messages. There was another surprise to come in our course on "Information Theory", where on the subject of "data compression", I learnt that the most frequently used letters should be encoded with the shortest "dot-dash" combination. For example the letters "e" and "t" are the most frequently repeated in the English language. The length of an encoded message would be shortened if the letters "e" and "t" were represented with the least number of symbols. My scouting classmates and I grasped this point at once because the letters in order of frequency: "e", "t", "a", "n", "o", "s" had already been represented by Samuel Morse, way back in 1844, as "dot", "dash" (single bit), "dot-dash", "dash-dot" (two-bits), "dash-dash-dash" and "dot-dot-dot" (three-bits) One test for the First Class badge was a hike in another town. The hike included camping overnight. I took this test with Ti Teow Kong, who was later to become Professor of Surgery in the University of Malaya and then in the National University of Singapore. We took a train to Port Klang (Port Swettenham then) and then hiked to Klang along the road which was flanked by a large water pipeline. Unlike the K.L.-Klang portion of the road, which was well shaded by rubber trees, the five-mile P.S.-Klang stretch was open to the sky and the hike would have been hot and sweaty had the sky not been overcast. Our rucksacks were not too heavy because Father bought his scouting sons a light-weight tent, which I was carrying along. It was a mail order purchase from an army-disposal shop in England whose advertisement had appeared in an English magazine. When the order arrived, we concluded that it must have been used by parachutist regiments. We chose high ground in Klang High School to pitch tent. Each end of the tent stood on hollow copper rods, about a quarter of an inch in diameter. The rods could be dismantled into lengths of about one foot long for packing. The tent cover was made of strong, synthetic fibre, which must have been the same material used for parachutes. The tent was held in form by the tension of guy-lines pulling the cover to ground against the copper rods propping it up. The mail order included aluminum pegs to anchor the guy-lines. The heaviest item in our rucksacks was the waterproofed, canvass ground-sheet, on which we slept. The overcast sky, which gave us shade in the afternoon, gave us a steady drizzle in the evening. The tent cover, which was light-weight to the extent of appearing translucent, was certainly adequate for an English drizzle. Fortunately, we were not put to the test to discover if it was good enough for a tropical downpour. The year 2007 will be the centennial year of the founding of the Scout Movement. Because many of the ideas of Baden Powell have been adopted in modern education, not to mention Hitler s Youth and Young Pioneers, it is easy to forget that he had good insight into the ways the young think. I cannot help marveling how he could keep us Wolf Cubs interested in going to Cub Meetings by re-enacting yarns from Rudyard Kipling s "Jungle Book". Castle Camp

The Image Gallery in the V.I. Web Page has a 1930 photo of Scout Master Mr. Lim Eng Thye seated with V.I. Scouts at Castle Camp. This photo dispelled all my previous conjectures of what had been the origin of the "ruins" as there never had been castles in the history of the Malay peninsula. Was it an architectural project which hardly began because the contractor absconded early with the funds? Or was it aborted because of the Great Depression? From the 1930 photo, the "ruins" of Castle Camp were concrete arches which looked more like a Roman aqueduct rather than a castle. Try as I did, I could not fit the arches to the local scene: unfinished Istanas (palaces), hospitals and mansions which were built in Malaya before the 1930s. Therefore, I was forced to conclude that the concrete arches were designed for the Boy Scout Association to suggest a castle, just as a few sparse props on stage are sufficient arouse the imagination to fill in the rest.

Castle Camp was located at the elbow bend of Rifle Range Road (now Jalan Padang Tembak), next to the Police Barracks. Our Scouting days were during the early 50s, the time of the Emergency, when the Police had more than civilian duties. Police patrols issued forth from the Police Barracks in the anti-communist campaigns. Around its premises were warnings: with the words "Protected Area" and a line drawing of a trespasser being felled by a rifle-aiming sentry. The Technical College (which later became Universiti Teknologi Malaysia) was located opposite to the elbow bend of the road, which changed its name from Rifle Range Road to Jalan Gurney (in honour of the British High Commissioner, Sir Henry Gurney, who was assassinated at Fraser's Hill), and most recently to Jalan Semarak. Later in the 1960s when I became a lecturer of Maktab Teknik (Technical College), I noticed that the coffee-shop which stood between the entrances of the Police Barracks and Castle Camp was no longer there. Since the coffee shop held memories of roti kaya which I sneaked out to buy whenever I became hungry because of my camp cooking, I was curious to know what happened to it. I was told that the people of the coffee shop had been arrested as spies for the communists, spies in such a strategic location. When we first came to Castle Camp, we did not know that we were so excitingly close to espionage. We were just excited to come under the spell of the name "Castle" and to spend a weekend in the "wilderness", away from home. Some fathers, who came to check out for themselves that the environment was safe for their sons, took a cold, adult look. They would have found, on entering the gate, a collection of shacks under corrugated iron roofs before they reached the aqueduct-looking, castle-ruins. One was the Scout-shop which sold scout hats, scout knives, compasses and books such as "Scouting for Boys" by Baden-Powell and "P.O.R.- Policy, Organization and Rules". Another was a store from which campers received cooking utensils, ground sheets and canvass tents. One large room was for meetings. The training courses for merit badges were conducted here. A large enclosure was sealed water-tight and the space within the four walls was flooded so that it became a swimming pool. Under shady trees and roof, the water was icy cold. Swimmers, who dived underwater, often surfaced with a fallen leaf or two on their heads. On the other side of the aqueduct-arches was a padang where Scout troops assembled. In the "Jamborette" and the "South-East Asia Patrol Camp", scouts from all over Malaya and neighbouring countries stood in the padang before their national flags. A clump of trees, with thick undergrowth, encircled the padang. Diametrically opposite to the flag poles, a "jungle path" led from the padang through the encirclement to the "Camp Fire Circle". The fire-place, where a log-fire would burn as we sang scout songs, was the geometric centre of Castle Camp. From this centre, concentric rings reached out to the perimeter fence, outside of which, encroaching suburban habitation was already taking away resemblance of wilderness. The innermost rings were the log seats, on which we sat, as we watched Skipper (Geoffrey Geldard - professionally a Straits Times journalist) muttered some incantation before saying, "I declare the campfire open," upon which the smoldering logs would magically leap into flames. Although reluctant to leave the children world of magic, by the second campfire, our eyes were on the lookout of the sleight of hand which hurled the cup of methylated spirits. We learned quite a collection of camp-fire songs, many of them brought home from international Jamborees (most recently, a V.I. King Scout was in the Malayan contingent to Austria). Skipper invariably led us through the "Ghost Song". "A woman to the churchyard went, " he would begin. We were to interleave it with the choral line, "Oo-oo-oh! Ah-aa-ah!" intoned as spookily as we knew how. "Very old and very bent." "Oo-oo-oh! Ah-aa-ah!" So it went. By the end, we became very aware of the moving, eerie shadows cast by the flickering flame on the waving branches of the ring of trees behind us. The camp-fire ended "Taps". We stood at attention and sang. Gone the sun. From the hills, From the sky, From the sea. All is well, Safely rest, God is nigh." It would have been better if someone could bugle the tune. Then we dispersed. We had to remember the layout of the camp in order to find our way back to our encampment in the dark. The camping sites lay in the annular space between the ring of trees around the camp-fire and the fence. The annular space was divided by radial clumps of vegetation into sectors to which visiting troops were individually assigned. Using flashlights, we had first to find the ring footpath which ran through the camp sites. Each sector had an attap-covered "long house", raised on stilts. We lay on ground sheets spread on the raised wooden floor of the "long house". (The possible reasons for the "long houses" were: (1) there were not enough tents to go around and (2) during rainy seasons we would be flooded out of our tents anyway.) For a good quarter of an hour, there would be talking and laughing in the "long houses". Some sleepy head would shout, "Shut up". There would be more whisperings. With Skipper s "Ghost Song" very much in our mind, each hoped that he would not be the last to fall asleep. Camping and Hiking My memory of the earliest camping days was of the belly-aching from boys who were miserable because they forgot to bring this or that, which they considered essential to their well-being. After borrowing from their more provident friends, they, just as quickly, forgot to return them, thus multiplying the misery all around. Fortunately, this phase passed after a few camps. We quickly learned to make mental check-lists of all the things we must bring. The hardier but still forgetful amongst us learned to disregard the discomforts brought about by overlooked items. Others just dropped out of camping activities altogether. From then on, camping began to be fun. Camping, which meant living together, forced us to broaden our outlook. When we cooked the first pot of rice in camp, it came as a shock that the way of doing things at home was not sacrosanct. Different families had their particular ways of washing rice and measuring the amount of water required. Our family would allow the water to rise to the level of the wrist, the palm being pressed against the top of the rice in the pot. Other families measured the depth of the water by the middle finger, the level having to rise to the second joint. Our family liked the cooked rice, soft and soggy. Others preferred granular texture. It was the beginning of a life-long lesson on "Vive la différence!" (Long live our differences). Our multi-racial society posed food problems which sometimes were difficult to resolve. An extreme example was our week-long camp on Langkawi Island. Adding to the well-known Muslim and Hindu dietary laws were the dislike of goat meat by the Chinese and of fish by the Sikhs in the troop. We were reduced to sayur kangkung fried with sambal belacan (shrimp paste) and eggs. Chicken was the most expensive meat in those days and was considered unaffordable. During the long train journey home from Alor Star, everyone was smacking his lips for home cooking and the forbidden food which he missed. Living away from home at this early age forced us to grow up faster. From living closely together, we learned about human characteristics: who were dependable and who were shirkers. These were lessons, which cannot be learned from text books. As a matter of fact, the better MBA schools recommend Outward Bound Courses to late developing students to receive the same exposure which we did while camping and hiking. My memory of the first hike was to Loke Yew Hill about a mile or two from Castle Camp on the first Sunday morning. The route was along a foot-trail through lalang and then across red, eroded laterite ground. Loke Yew Hill was a small hill, on the summit of which were the grave, the tombstone of tin-magnate Loke Yew, his statue and Chinese pavilions, all of which were much desecrated by graffiti. From high ground, we looked over the Klang-Gombak flats which had been worked over by tin dredges and were then covered by elephant grass. In a distance was the lime-stone out-crop of Batu Caves. On return to Castle Camp, I found my stockings covered with grass seeds whose hooks had latched on to the wool. I spent a good twenty minutes literally "nit-picking" and disseminating. I was quite annoyed because the hooks of the grass seeds were difficult to dislodge and my brute-force method left the stockings fleecy.

My first camping trip outside Castle Camp was to the 8th mile of Port Dickson (P.D.) during the school holidays. As Alexander Lee was in the 1st K.L., he invited us to camp on the beach front of his father s (then Colonel H. S. Lee) seaside bungalow. Alex, as we called him, excelled in aquatic sports in the V.I. swimming pool, specializing in the butterfly stroke. In P.D., Alex spent much of his time water-skiing, with his older brother Douglas, on the motor boat, towing him. Before completing Standard Six, Alex left V.I. for his secondary schooling in England. I never met Alex again. I knew about his recent death only because my brother, Boon Leong, sent me a newspaper cutting. I was struck by the fact that in life and in death, Alex was close to the water sports which he loved. Our P.D. camps thereafter were on the grassy patch amongst the fallen needle-like leaves of the casuarina pines in the vacant land next to H. S. Lee s bungalow. We fetched water from a roadside tap, which was a source of potable water to a nearby kampong. After the last swim, I liked to rinse myself of brine and would go to this roadside tap to do it. I remembered a kampong woman who came to fetch water but had to wait until I completed my wash. Her patience and courtesy left a deep impression on me because I was interrupting her daily routine even though I was using a public tap. When I was an undergraduate in the University of Adelaide, I boarded with Mrs. Johnson, who happened to be a Girl Guide Leader. One day she took me to visit a camp. One of her Girl Guides offered me a mug of tea. The first sip, with the flavour of wood smoke in the brew, rekindled powerful memories of Castle Camp. Besides the nostalgia, I had stumbled into discovering the origins of a family of food: smoked salmon of the Haida of British Columbia, smoked meat of Lithuanian Jews, Hunanese smoked duck. Slow Boat to Singapore and Langkawi Island Although I was in the 1st K.L., the 2nd K.L. Scoutmaster, Mr. Chin Peng Lam, invited me to join his troop on their visit to Singapore. This was in 1952 or 1953. It was very thoughtful of him because he knew that I would be left out when my brothers, Boon Leong and Boon Seng, both in the 2nd K.L., set off on this holiday trip.

Peng Lam had the charisma of a youth leader and with Kamarul Ariffin, the 2nd K.L. outshone the 1st K.L. Peng Lam was for some time a teacher in the V.I., specializing in teaching "Art". Later, he left the V.I. to become a Police Inspector. A few outstanding scouts of this period were Khoo Choong Keow, Shanmughalingam, Yoong Wah Pin. My memory of this visit to Singapore was mostly on the unusual outward-bound journey because we traveled by train to Port Swettenham and then boarded a cargo ship, the S.S. Tung Song. Tung Song steamed southwards on the calm waters of the Straits of Malacca, a voyage which took a day and a night. We were not able to see Sumatra, as the ship kept close to the coastline of the Malay Peninsula which appeared as dark edges to the sea. Sometimes, there were patches of white beaches and I kept wondering if my classmates were not bathing there as I knew of their plans to go the Port Dickson during the same holidays. For most of the time, we enjoyed the sea-breeze and kept watching the long wake churned up by the propellers. The hand grenade-size jelly fish, which we would avoid at all cost when swimming along the beaches, took on the sizes of drums and table-tops in open sea. As they bobbed up and down on the waves, exposing their innards through their transparent outer covering, they looked equally obscene, whatever their sizes. I am reminded of this first encounter with the jumbo-size jelly-fish every time I am treated to the Chinese cold dish, which paired cold cuts with jelly fish. The setting sun cast long shadows of the waves. Later in the darkness, the froth on the wake whitened in fluorescence. We slept in open-air on the aft deck on a tarpaulin spread out for our use. By the next morning, we transferred from the Tung Song to lighters which landed us on Clifford pier. In those days Singapore River was full of lighters and stench. We stayed in the YMCA and made daily sightseeing trips. We cooked in a camp kitchen set up in the back verandah. We must have returned by train but I have no recollection of this journey. In 1953 or 1954, when I was a Senior Scout, the 1st K.L. Troop, under Wong Peng Kong as Scoutmaster and Mohammed Nasir as Assistant Scoutmaster, made a trip to Langkawi Island. We took the train to Alor Star and then a motor launch down the Kedah River to open sea and then across to Langkawi Island. I was hoping to see a crocodile along the Kedah River but I only spotted an odd log now and again. The sightseeing along the river trip consisted of looking at mangroves and nipah palms. By the time we reached the open sea, it was dark and I fell asleep. By the next morning, we arrived in Kuah, which was then a small village facing the mainland. We camped at Kuah. After settling down, Mohammed Nasir berated us for falling asleep when there were ladies traveling on board with us in the launch. According to Nasir, the proper etiquette was to be respectfully awake. Looking back, I am grateful for this lesson on chivalry. (Nasir invited us to his home in Kampong Baru on several occasions. A most memorable one was a family wedding, when I had the privilege of witnessing all the relatives pitching in on cooking and preparing the wedding feast gotong-royong.) There was only one tourist, apart from us, in Kuah. He was a young professional, newly returned to Malaya after earning his degree abroad. We could not understand why he was so lyrical on the beauty of Langkawi. To us, Langkawi was just like the rest of Malaya, no big deal! There was a stretch of sandy beach but so had Port Dickson. As I just saw the film, "Return to Paradise", the story based on a South Pacific island, I was humming the theme song but not truly convinced that Langkawi was in a paradise setting. It would require us to be travellers abroad and return home, like the young professional, to discover the beauty we take for granted. Scouts in our patrol - I remember Lee Choong Loui amongst them - kept ourselves busy by cooking and scrubbing the aluminum utensils with steel wool until they were spotlessly clean and shining. As I mentioned previously, we had a minor problem of finding the food which satisfied everyone s religious observances and personal preferences. Other than that, we were enjoying ourselves. One day, Mr. Sadhu Singh, a teacher who came with us, had a talk with us. He told us that we should not be so occupied with maintaining high camping standards, but to take time to laze around as tourists. Around the last day of our camp, a local entrepreneur organized a mouse deer hunt for a modest fee. One side of the jungle was fenced in with netting. All of us and some locals were lined up on the other side. At a given signal, we shouted, banged pots and cans and advanced through the jungle towards the net, frightening the mouse deer which fled before us until they entangled on the net. The locals would grab the deer, whose hearts could be seen palpitating wildly. They immediately defanged the captives by forcing the protruding tusks against the trunk of a tree. The mouse deer au naturel look unseemly because the tusks are out of place on such an endearing animal. To us, the disarming of their offensive weapon was an esthetic surgery. To the locals, the tusked mouse deer could still cause dangerous accidents. Peng Kong carried a deer home in a wooden cage, in the hope of keeping it as a pet. But it died not long after. Today the mouse deer is a protected animal and presumably the brutal hunt is outlawed. International Scouting As my two brothers in the V.I. were in the 2nd K.L. and another brother, Boon Keng, in the Methodist Boys School (MBS) was in the 10th K.L., scout troop rivalry was not in the forefront of our awareness. We were more conscious of competition from other youth groups such as the St. John Ambulance Brigade. In 1953, the V.I. Cadet Corps was revived under teachers Mr. Herman de Souza and Mr. Lai Nyen Foo. Lee Choong Kit, later School Captain, led the Corps in the marching drills and stole our thunder. Within the scout movement we were more aware of brotherhood-fostering activities such as the Jamborette and the South-East Asia Patrol Camp. Both of them were held in Castle Camp. The Jamborette followed the World Scout Jamboree in Austria and as the name implies, it was a local, mini-jamboree drawing scouts from all over Malaya and Singapore. Through the Jamborette we came to know that there were scouts from ulu (Malay for hick) places. My K.L. civic pride was offended when some bumpkin asked me if he had to boil the water from the tap before drinking. There was a trail-following game which took the campers to explore the streets of Kuala Lumpur and gave them the excuse to gawk at the skyscrapers, the latest being the Loke Yew Building which rose a floor or two above the four storey-high Oriental Building (which held the record for altitude for a decade or more). The South-East Asia Patrol Camp drew contingents from French Indochina (now Vietnam), Cambodia (now Kampuchea), Indonesia and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). The anti-Communist security forces in Malaya then had battalions from Fiji and Africa. A number of servicemen, who had been scouts in Fiji, formed a contingent. There was a scouter from Swaziland (a landlocked country in southern Africa) and another from Nyasaland (now Malawi). It was a year or so before the battle of Dien Bien Phu, when General Giap defeated the French. Except for a token Tonkinese or two, the patrol from Indochina was made up of French boys. I was present when the patrol of French boys arrived at a reception booth. It was already dark and some wicked person had placed a toy snake on the dimly lit counter and moved it slightly so that it seemed to slither. Thinking that it was alive, one of the French boys gave a yell in fright. Apparently, Prince Sihanouk retained greater control. The Cambodian contingent was made of Cambodians, who kept repeating Kampuchea to correct us each time we referred to their country as Cambodia. The Indonesians flew a flag which was larger than the others and were proud of their political independence: the rest of us were still living under colonialism. The contingent from Ceylon was led by a Scout Commissioner, whom I recognized some twenty years later in the streets of Montreal. Amongst the highlights of the Jamborette and the South-East Asia Patrol Camp were the camp-fires when we exchanged our repertoire of scout songs and scout yells. We came to take a liking to Malay favourites, Chan Mali Chan which began with "Di mana dia anak kambing saya?". Another was "Tukang talit eh, banyak untong. (Help! I have forgotten my Malay and the title itself.)" Local flavour was added to the foreign imported yell, "Chika-laka, chika-laka, chow, chow, chow". The Hokkien dialect fitted in nicely with, "Chika-laka, Chow kuey teow (fried rice cake), Chiak beh leow (cannot eat it all), Si keow keow (really dead)". We were taught a Swazi yell, "Een-gonyama, gonyama. Invooboo. Yaboh! Yaboh! Invooboo" which translated as, "Look, there s a lion! No, it is not a lion. It is a hippopotamus!" From Nyasaland, we were told that simba was Swahili for "lion" and we learned an enactment of a lion hunt. It would be interesting to know how Chin Peng and his Communist terrorists rated the Fijians as jungle fighters compared to the Gurkhas. Certainly, the Malay Mail gave them good coverage as rugby players. In ceremonial occasions, they wore deeply serrated, calf-length skirts as their military parade uniform. The Fijian contingent belonged to the age group of Rovers. In the camp, they introduced us to Polynesian rhythms and songs sung with miming gestures of the hula family. I can only remember the first line of one song, "Ee papa wah.." Unlike my brother Boon Seng, I never had a memory good enough to recite the complete lyrics of any Fijian song. In the following year or so, there was a Jamborette held in Colombo. But my Father would not let me go. As a sweetener to the disappointment, he told me that it was better to defer travels to adulthood when there would be more avenues to enjoyment. Another international encounter was when the V.I. scouts hosted a visit of Thai scouts. Each of us was paired to a Thai visitor. After sightseeing, my brothers and I invited our Thai partners home. While waiting for dinner, I took out a parlour game board which I had recently received as present but had never played before. I read the rules and we taught ourselves to play the game, which was "Chinese Checkers". How we managed was quite a wonder because for most of the time we communicated by gestures! The Thai visitors came prepared with a Thai song to teach us. They had brought along English lyrics, so that we could sing along: When shines on earth. It looks better, When (you) dance with me. We dance for fun. We shun possible worry Join us, be merry, With Thai folk song." For the sake of international goodwill and friendship, we managed to keep very straight faces while we sang to the meandering folk melody. This group of Thai scouts had gentle, well-brought-up manners. My Father (late Dr. Ooi Keng Seng) took a liking to them too, so much that he threw a party for us. He booked the upper floor of Mohammed Kaseem on Batu Road and treated the seventy or so hungry scouts to Indian-Muslim curry-fried chicken, beef rendang and nasi briyani (yellow rice). Job Week The concept of Job Week started in the early 1950s. In the Britain, the idea of Boy Scouts raising funds through doing odd jobs for families made sense since the employment rate was high and there were no domestics to do house-work. In middle class Malaya from which we came from, the domestics thought it hilarious that the young "masters" would go soliciting for the opportunity to do the menial tasks which they were doing for a living. The natural territory for job hunting was along Circular Road and Maxwell Hill, where the British "expatriates" had their bungalow houses. My first successful find was at the corner of Circular Road and Freeman Road where I earned 5 ringgit for grooming two dachshunds. A brush was thrust onto my hands and, fast learner that I was, I quickly learned the grooming strokes which their mistress taught me. Before long, every Scout Troop invaded the same territory and the repeated job-week hunting calls became a nuisance to the good people. V.I Scout Show In one year, both the 1st and 2nd K.L. troops put on a joint Scout Show. The fun part was in the rehearsals and the work associated with the staging the show. The part, we disliked intensely, was in the selling of the tickets. We had to accost strangers in a Mounbatten Road street corner and learn to accept rejections. Mostly we depended on our families and family friends for our audience. This show was staged in the school hall, which was noted for its bad acoustics. In one item my brother, Boon Leong, was the "compere" of a fashion show.

Mr. Chin Peng Lam, the 2nd K.L. Scoutmaster, had a mysterious act in which a scout would poke his head momentarily out of the curtain on the right-hand side of the stage and in a split second reappeared from behind the curtain on the left hand-side. Then another head appeared and repeated the fast disappearing and reappearing trick. Our Mother, who was always drawn to support her sons activity, later told us that she thought the boys had run across the stage from left to right side behind the curtain. At the end of the act, the "actors" came out from behind the curtain to take their bows to the audience who realized that the act was made possible because the 2nd K.L. had two pairs of twins, the Eurasian twins and a Chinese pair. Peng Lam suggested that we, in the 1st K.L., could put on a skit based on the 78 rpm record, She Wears Red Feathers and a Huly-huly Skirt. Some parts of the lyrics, which I can still remember, are: She wears red feathers and a huly-huly skirt, She lives on just cokey-nuts and fish from the sea, A rose in her hair, a gleam in her eyes, And love in her heart for me. "I work in a London bank, respectable position, From nine to three they serve you tea But ruin your disposition, Each night of music calls, rather lost I seem, And once a pearl of a native girl came smilin' right at me...." There were four rather rotund scouts in the 1st K.L., namely Khoo Teik Kooi, Sujit Sen, myself and a fourth, whose name I have forgotten. Peng Lam encouraged us to make up a mime-dance routine which enacted the lyrics. So we did. Once again, Grandmother was recruited to help us by tailoring four mini huly-huly (possibly a cross between hula-hula and hurly-burly) skirts from red and green chiffon-like material. We cycled to Gian Singh, which sold women's underwear, and each bought a brassiere for the upper half of the costume. We had a red headband to fasten the red feathers. We knew that the costume alone was good for laughs. In the 1950s, we were not yet saturated with entertainment media and as the level of sophistication was not high, our act was much appreciated. The Gang Show The Gang Show was staged in 1951 in the Chinese Assembly Hall which, at that time, held the largest stage and seating in K.L. The show drew the British elite of K.L., who came in jacket and tie in an unusually hot steamy night. Looking back, I have wondered what was the reason for this large turnout. Was it because the Gang Show in London had just given a Royal Command Performance? The K.L. Gang Show was in the tradition of the London Gang Show. It was Ralph Reader who started the Gang Show in England in 1932 when he was a Rover Scout. Many stage and film stars had their beginnings in the Gang Show, for example Sir Harry Secombe, Sir Richard Attenborough, Peter Sellers, Darryl Stewart, Max Bygraves, Spike Milligan, Norrie Paramour, Dick Emery, Tony Hancock. The K.L.Gang Show drew hundreds of scouts from all the troops of K.L. I was in the chorus, which was directed by Johnny Cardosa from St. Johns Institution. He had a good singing voice and could accompany himself with an accordion. At that time he was just another European or Eurasian teacher to me. Now, with the present president of Brazil having the same name, I conclude that he is of Portuguese lineage. The rehearsals were very frequent and looking back I am surprised that it did not draw any reproof from Father that I was taking too much time away from homework. We rehearsed two major songs: Chewing Gum and Zither Melody. The parts of the lyrics of Chewing Gum, which I can remember, are: Chewing gum, Chewing gum "My mum gives me a nickel To buy a pickle I didn t buy the pickle I bought some chewing "My pop gives me a dollar To buy soda water I didn t buy the water I bought some chewing "I chew the day away, it seems I am blowing bubble in my dreams ......" I found it contradictory that during one campfire, Geoffrey Geldard (or Skipper ) told off a scout for crooning a cowboy song and that he should be singing scout songs instead. Evidently, the tide of American culture could not be held back. The Zither Melody was the theme music composed by Anton Karas in Carol Reed's 1949 film, The Third Man. They found someone who could twang the zither (laptop string instrument) strings during the Gang Show. One standby trick of music hall is to play the tune again and again because the mind must have the chance to memorize the melody before it can take a liking to the music. Thus, we sang the "Zither Melody" several times as an action song, interspersed with other acts of the variety show. To this day, I can remember all the lyrics of the very haunting melody: Everywhere you go, they play Very, very soon, this fascinating tune Steals your heart away Once you hear the sweet refrain It will run around your brain To this theme, you dream a dream All the while, a swaying to and fro First it makes you feeling sad And then sing merrily You ll love the zither melody (At this point, the pace quickens and the song picks up the strumming of the zither) There's a man who plays the zither Like you've never heard it before He wrote the melody String notes and harmony You will adore. (Returns to leisurely melody) With a feeling of real romance When you hear him play I know that you'll ask for more You never dreamt that you could be Haunted by a melody Something that's completely new I m warning you It will thrill you through and through The zither melody is rare It simply fills the air It's with you all the time To the theme song of Harry Lime." (repeat) Backwoodsman Test In order to win the Green Cord (the equivalent of King Scout) in the Boy Scout category (12-15 years old), I had to get 6 proficiency badges. I had already passed the First Aid, Missioner, Cooking badges and two others. The last badge on Backwoodsmanship was mandatory. Amongst other trials in passing the Backwoodsman test, I had to kill a live bird, cook it without a utensil and eat the cooked bird. As someone who preferred inanimate objects and became an engineer in adult life, I was never comfortable with handling the warm bodies of a bird or a mammal. I dreaded the thought of a fowl in my hand, as it twitched and turned, in the last throes of its existence. But because I was face to face with my own cowardice, I could not turn back. So one Saturday morning, I bought a chicken from Pudu Market, cycled along Circular Road and then along Gurney Road and brought it to Castle Camp. Seeing that I was nervous, a Rover Scout from a Malay troop, which was camping there for that weekend, offered to kill the chicken for me. "No, thank you," I told him politely. I was not going to chaang Cheong, I said to myself. (Chaang Cheong in Cantonese roughly means "paying Mr. Cheong to do something which one does not have the ability to do") So I began to follow all the procedures which I had watched the cook do in the kitchen as she prepared a chicken offering to be placed at the family altar on a feast day. With my left hand, I caught hold of the head and arched the neck so that the throat protruded forward. With my right hand, I plucked away the feathers so that the skin was exposed. Then I unsheathed my scout knife, put the blade against the throat and applied slicing motions. But nothing happened! Not even a trickle of blood. In the post mortem (mine, not the chicken s), I concluded that either I had not removed all the feathers on the throat or I never learned how to sharpen my scout knife. The latter was the more likely possibility because in Mrs. Dempster's Biology Laboratory I never succeeded in preparing a microscopic slide of any specimen, one layer of cell thick, because my razor blade was never sharp enough. Returning to the narrative, by this time my courage left me. I knew that if I botched it a second time, I could end up chasing after a chicken with a half-severed head. All this time, the Rover Scout was watching me. I did not turn down his offer a second time. I accepted my cowardice and consoled myself that chaang Ahmad might not be so disgraceful as chaang Cheong. The Rover Scout said a prayer and slaughtered my chicken according to Islamic rituals. I thanked him profusely. He was no doubt happy with the thought that he had not only done his "good turn" for the day but assured an infidel of a halal meal as well. I still had to convert the carcass into a meal. I took it to a spot next to the banyan tree in Castle Camp. Following the instructions of a scouting handbook, I disemboweled the bird and plastered the body, feathers and all, with mud. It had rained the previous day and the ground was wet and soft so that it was easy to scoop out the mud. Then I planted the chicken in the ball of mud in the hollow and built a fire over it. After a few hours, I cleared away the embers to recover the mud ball. When I cracked the mud shell, the feathers which were stuck to the shell tore away from the soft, tender and moist flesh. I did not recapture the delicious taste of "mud chicken" for a long time. As a university professor, I am allowed certain eccentricities, but re-creating the "dish" in mufti and in the home kitchen was stretching the limits. Then one day, as part of my culinary exploration, I selected from the menu, Dong Jiang Chicken (Dong Kong in Cantonese for East River - which meant that the dish was of Hakka (guest people) origin). I was informed that in the restaurant the chicken was encased in dough which sealed and retained the moisture. As a purist and always faithful to my first love, I was not sure if the herbs, which the restaurant cook threw in, added or detracted from the flavour. Sir Gerald Templer This day of my Backwoodsman badge test was eventful because while tending the fire, we had a surprise visit from the Chief Scout himself. General Sir Gerald Templer, Knight Commander of St. George and St. Michael, was accompanied by Lady Templer and their daughter, Jane, all dressed in Scout uniform. I looked around for the ADC, aide-de-camp, because my father told us that daughters of high officials end up by marrying the ADC. There was no accompanying ADC.

I have often wondered what took this highest civil and military official of British Malaya to Castle Camp that day. No doubt, it was British policy to prepare Malayan youth for leadership for the coming independent Malaya, and youth movements, such as the Boy Scouts, were given official support. But if Templer had any intention of giving encouragement by a public appearance in Scout uniform and all, the press was noticeably absent. As the archives would testify, Templer was not naïve on the role of the press in conveying a policy message. If his intention was to come unexpected to make a personal assessment of the strength of the Scout Movement, he was not exactly coming incognito. The Templers, all of them tall and wiry, did not survey us at a distance. They came and asked us what we were doing. Seeing that we were cooking, Sir Gerald told us his cooking experience during his scouting days. He could not eat his cooking, he said, and the punch line was, neither would his dog. This visit made a deep impression on me. I marveled at his immense energy: how in what must have been a very heavy schedule in fulfilling both military and political missions, he would stop by to meet young boys like us. I followed his career, after he left Malaya, to become Field Marshall and Chief of the Imperial General Staff. Slander: Duffers and Wasting Time In our time, a slander regarding scouts was that they were recruited from the duffers in school. The corollary was that they should be catching up on their studies, instead of standing on duty during sports days, royal visits and state funerals. I wanted to rebut this slander and waited for the opportunity to make the statement. My idea was to march up the stage in my scout uniform before the assembled school on Prize Giving Day and take the three-finger scout salute as I was awarded the most important scholastic prize of the school. But on the day, when this rebuttal could be made, in the Prefect Board Meeting, the School Captain told us to come in prefect uniform. On Prize Giving Day every year, the assembly of pupils would be seated on the floor of the school hall, under the watchful eyes of the school prefects standing in their white uniforms, one prefect at each of the many doors on the two sides of the hall, which opened to the school yard. I knew that the School Captain would see a scout uniform as a disruption of the neat array of white coats and white trousers. Having a nearly-Confucius upbringing to be unquestioningly obedient, it never occurred to me that I could ask the School Captain to be exempted. As a result, I received the Rodger Scholar award in school prefect uniform. Yoong Wah Pin, who was King Scout, scolded me for letting the scouts down. After so many years, I still remember Wah Pin's scolding and only wish that I had been more self-assertive. The criticism about not studying enough and wasting time could be countered by: "all work, no play " makes duffers into dullards. Most of us enjoyed being called up on official functions because it allowed us to be on the "ring-side seats" of major events. Unknown to us then, we were witnessing the "pomp and circumstance" of the last days of the British Empire. I left Malaya for studies abroad in early 1957, so that I missed the first August 31st celebration in the newly completed Merdeka Stadium. However, a few months before Merdeka, scout duty took me to "PESTA", a prenatal, national celebration of Malay culture. "PESTA", as the name suggests, was a fiesta, which brought Malay cultural performing groups from all the states of the Federation to Lake Garden. Each group had its stage designed in Malay architecture, with its regional style. Beside the red Japanese bridge, around the lake and over the gentle mounds, the many stages transformed Lake Garden at night into a fairy land with their festoons of multi-coloured lights. Until then, my knowledge of Malay dance and music was limited to ronggeng and joget moden which were commercial entertainment in Shaw Brothers Bukit Bintang Amusement Park (B. B. Park). Once a year, the Malayan Agriculture and Horticulture Association (MAHA) held an exhibition in Kuala Lumpur and I would know a bit more of Malay arts and crafts every time Father took us to MAHA. The feast of culture at "PESTA" was so overwhelmingly rich and diverse that I could not take it all in, during the night when I was on duty. So, I went again by myself during the next evening, this time off-duty. It was only very much later that I learned that there were influences from neighbouring Indonesia. I came to know of Gamelan music from Bali which attracted the interests of Zoltan Kodaly and Bela Bartok. (As a matter of interest, the University of Montréal has put on an annual Gamelan Concert during the past few years.) Besides discovering more of our own culture, it was also a self-discovery that I liked folk culture. This was the beginning of my life-long interest in folk dances and folk music from all the continents. In my travels and my job assignments in different countries, I easily made friends because I wanted to learn their folk dances. A Summing Up

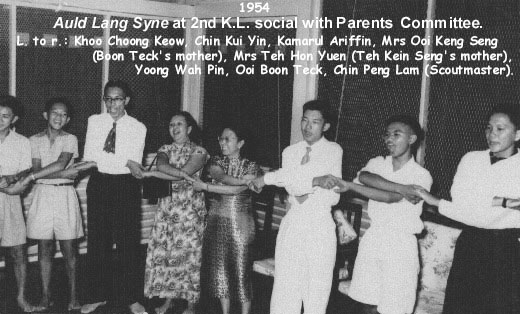

As to duffers, the scouts must have its share of the statistical distribution in the school population. During my brother Boon Seng's last trip to Montréal from Washington D.C. to visit me, in the year before his fatal stroke, we talked about our scouting days. Boon Seng remembered one scout who fell in the category of potential never-do-well. It was a case of someone coming from poor economical background, with little family guidance. Left to himself, this person would have just drifted. But scouting gave him role models and direction so that he succeeded in a good career. Boon Seng's conclusion was that although scouting was important in supplementing the guidance and care which our parents had been lavishing on us, our case was in no way comparable to the contribution which scouting made to the life of this person. Much of the credit, for having scouting memories to look back to, belonged to Scoutmasters. Ours were Chin Peng Lam and Kamarul Ariffin of the 2nd K.L., Wong Peng Kong and Mohammad Nasir of the 1st K.L. Peng Lam has a special place in the hearts of my brothers, Boon Leong and Boon Seng, and myself. Besides inspiring the 2nd K.L., he initiated the only Parents' Committee of our time. Below is an old photograph taken during a social of the Parents Committee held in the residence of Kamarul Ariffin's uncle. Both Ariffin's Uncle and Aunt were most gracious host and hostess to Mrs. Teh Hon Yuen (Teh Kein Seng's mother) and to our parents. The importance of the Parents Committee was not in the advice and direction it gave. More important, it served as institutionalized acknowledgment by parents of the devotion of the Scoutmasters and since Scoutmasters were after all human, they needed continuing encouragement and support.

The V.I. Web Page

The V.I. Web PageLast update on 23 November 2003.

Contributed by:

Ooi Boon Teck

|