The unseen doctor:

Celebrating the life of Malaysia's

preeminent anaesthetist,

Dr T Sachithanandan

Eminent anaesthetist Dr T Sachithanandan

December 3, 2022

"Do you remember the name of your anaesthetist?"

I squint my eyes, furrow my brow and try to recall.

The man in surgical scrubs seated across the table smiles wryly.

"If you had any treatment, you'd definitely remember your surgeon, but you wouldn't know who gassed you, right?" he asks. It's a rhetorical question of course, but I still shake my head a little sheepishly.

"As a surgeon, I work with anaesthetists every day in the operating theatre. I genuinely feel that they're quite under-appreciated as a medical specialty," continues Dr Anand Sachithanandan, a cardiothoracic surgeon, vehemently. A pause, and he says quietly: "But I think my father did a lot to change that mindset."

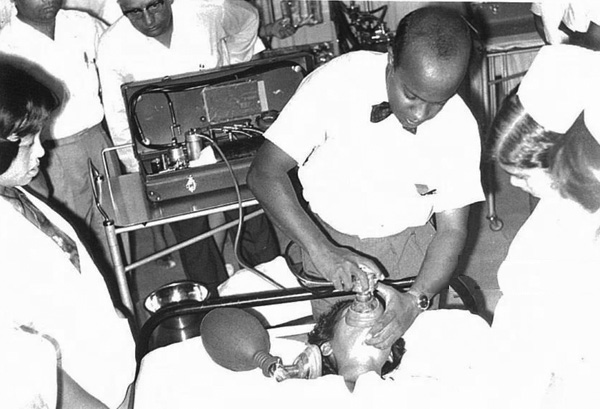

As he sits back in his chair, I catch sight of a framed photograph behind him. It's a picture of his father in similar scrubs performing neonatal resuscitation on a newborn at the Ipoh General Hospital in 1972.

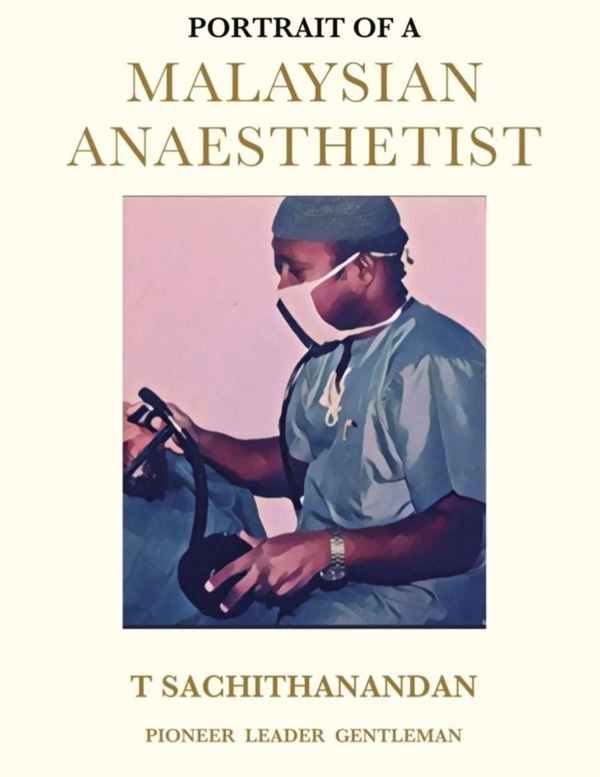

The late Dr T. Sachithanandan, a preeminent anaesthetist, features in Dr Anand's recently published biography, Portrait of a Malaysian Anaesthetist: T. Sachithanandan - Pioneer, Leader, Gentleman.

"You have to get used to being invisible as an anaesthetist," he says dryly. During an operation, your life is in the hands of the anaesthetist. But despite the highly sensitive role he plays, he's all but invisible to patients.

For prominent anaesthetist Dr Sachi (as he was fondly known), the contributions he made throughout his career have been largely in the shadows atypical of his profession.

One of the first Malaysians to qualify as an anaesthetist and the first to be elected president of the Malaysian Medical Association, Dr Sachi was responsible for the very first intensive care unit (ICU) opening its doors at the General Hospital Johor Baru (now renamed Sultanah Aminah Hospital) back in 1968.

It was the first ICU established in a Health Ministry government hospital in Malaysia, the first in the state of Johor, and the second of its kind after the ICU at University Hospital in Kuala Lumpur.

The visionary pioneer of intensive care, regional anaesthesia and postgraduate medical education in Malaysia, Dr Sachi's contributions were largely buried within the pages of medical journals, previously published medical books and newsletters until recently.

Portrait of a Malaysian Anaesthetist highlights many intriguing aspects of the anaesthetist's trailblazing career throughout the early years of the Malaysian healthcare system.

Some of the early local anaesthetists in Malaysia

For Dr Anand, the most precious thing his father gave him was an example of how to live a life of service.

"My father was a visionary and a leader, a man who respected and valued everyone, from royalty and politicians to hospital porters and domestic cleaners," he writes in his introduction to the biography.

EARLY YEARS

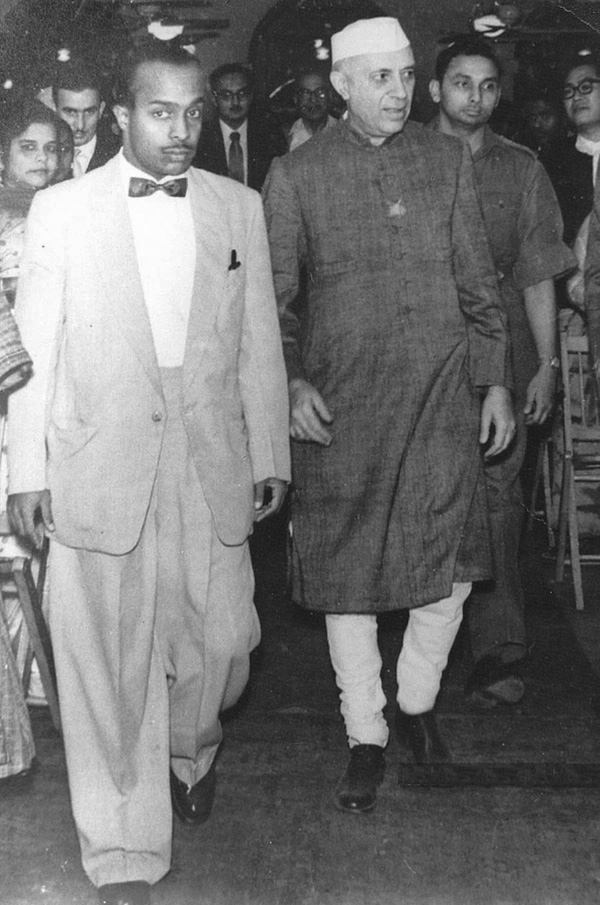

With Mr Jawaharlal Nehru, first Prime Minister

of India and a leading figure in the Indian

independence struggle (1957)

T. Sachithanandan was born in Kuala Lumpur, British Malaya, on Aug 2, 1931. The second youngest of four siblings to an upper-middle class Ceylonese Tamil family, the young boy studied at the renowned Victoria Institution of Kuala Lumpur and went on to enrol in the Loyola College in India.

A glimmer of his personality could be traced back to an old handwritten letter to his father. Sachi was selected to represent the college at the National Union of Students Conference in Delhi in 1952. He was the first foreigner and first Malayan to represent the college in this manner.

The conference provided an excuse for him to have a bespoke woollen suit tailored for the cold weather. He wrote to his father, saying that he had to "...at least dress like a gentleman as students from all over India will be attending the conference, and I must keep up to the dignity of the College".

Dr Anand laughs when I bring up that particular anecdote. "It's true!" he exclaims, continuing: "We found a folder of old letters that he kept meticulously. Some of the letters are old, yellowing and soiled. Thankfully they were mostly in English. His letters to his father were formal, but affectionate and they gave me a real insight into his personality. He was quite a stylish guy even back then!"

Dr Sachi was always well-dressed, favouring hand-tied bowties. "He was unconventional," agrees Dr Anand. "His very nature was flamboyant, but in a nice way!"

He graduated from Calcutta Medical School in 1957 and upon his return a year later, he joined the Malayan Medical Service on Aug 23, 1958. During his first posting at the Penang General Hospital, he met Dr L.P. Scott, a specialist who might have first piqued his interest in anaesthesia.

Another interesting episode in Penang would be when Dr Sachi bashfully declined an offer from a nurse to dance at the traditional annual hospital dinner and dance.

Dismayed by his inability to dance, the determined Dr Sachi promptly signed himself up for ballroom dancing lessons the very next week. It wasn't long before he became adept in the tango, foxtrot, waltz, quickstep, rumba, cha cha and the samba!

"This little episode highlighted his steely determination and drive to constantly better himself and succeed. He was never one to accept status quo. He constantly questioned if there were ways to circumnavigate limitations," shares Dr Anand.

Upon completing his housemanship, Dr Sachi spent the next two years serving as a medical officer in anaesthesia at the General Hospital in Alor Star, Kedah, before moving to the Kuala Lumpur General Hospital.

There, he had the privilege of working with Dr Frank R. Bhupalan, widely regarded as the "Father of Anaesthesiology in Malaysia". Under the watchful gaze of his mentor, Dr Sachi developed his core technical anaesthetic skills and gained his clinical experience.

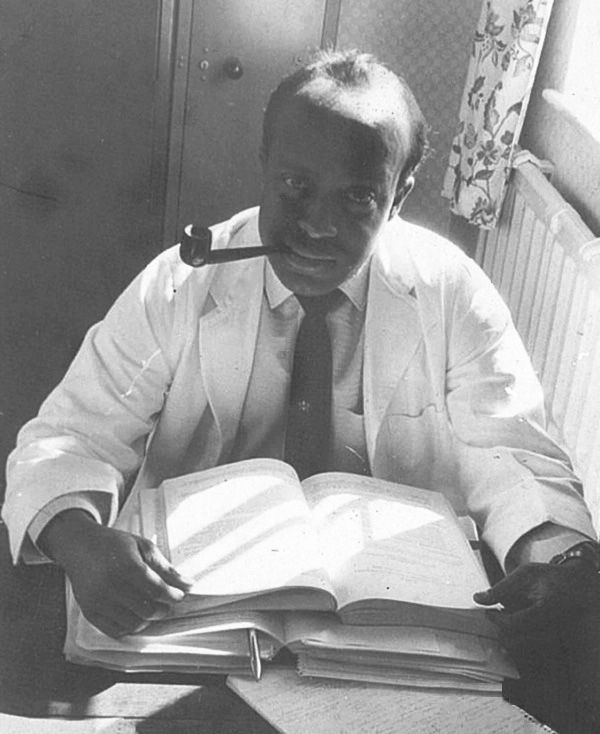

Prepping for the anaesthesia FFA

fellowship examination, London (1963)

In 1961, Dr Sachi travelled to the United Kingdom on a Malayan government scholarship for his postgraduate specialist training. He would spend nearly three years in England training with outstanding post-war British anaesthetists, becoming the first Malaysian doctor to undertake postgraduate specialist training in anaesthesia in London.

A beneficiary of training during the truly golden era in British anaesthesia, Dr Sachi would eventually pay it forward by training and mentoring the next two generations of local anaesthetists in Malaysia from the moment he returned home.

ICU PIONEER

The iconic Johor Bahru General Hospital, home of the first postgraduate

medical centre in the country (1969) and first ICU in the Health Ministry.

Upon his return from London in 1964, Dr Sachi swiftly recognised the need for a specialised unit to appropriately manage sick patients as there were no such facilities then.

At that time, following a major surgery, patients would be sent back to the wards or simply "observed" in the recovery room with minimal or no monitoring.

The anaesthetist had been training in the UK when a growing awareness and acknowledgement of the inadequate and inefficient care provided for patients with life-threatening conditions eventually led to the development of ICUs throughout the country. He saw first-hand how ICUs were making a difference in the lives of critically-ill patients.

"It was an unheard-of concept here in Malaysia. When my father was posted to Johor Baru, he observed that patients were not being appropriately cared for," says Dr Anand, remarking: "He was original in his thinking and not prepared to settle for the status quo. He saw the importance and need for ICUs, and started pushing for the setting up of a unit in JB since 1965."

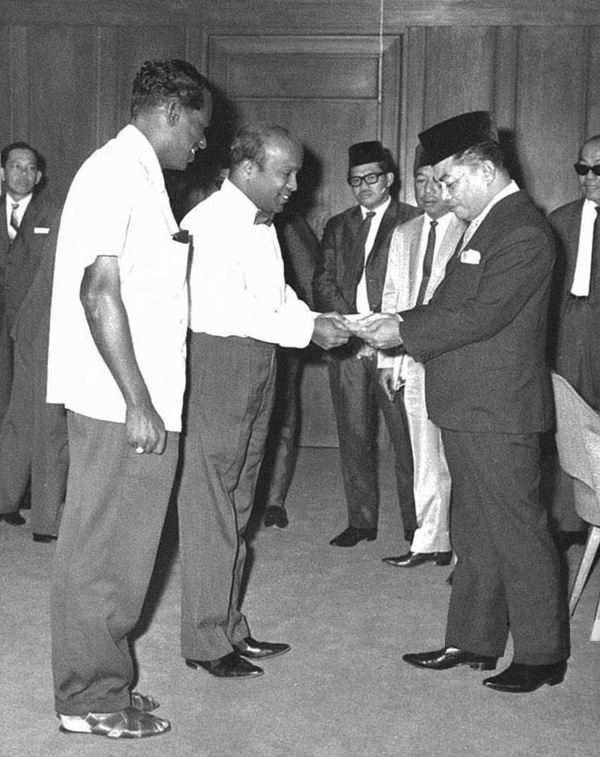

Receiving a cheque from Johor Menteri Besar

Datuk (later Tan Sri) Othman Saat. Funding from the

Johor state government was critical in the building

of the inaugural Intensive Care Unit.

With the assistance of the Junior Chamber International (JCI or Jaycees), a worldwide non-governmental organisation of young leaders and entrepreneurs (which Dr Sachi was a member), funding was raised and the ICU was built in 1968 at an estimated cost of then RM120,000.

The original eight-bed ICU created by Dr Sachi expanded to 16 by the early 1990s. A decade later, this 32-year-old pioneer ICU was permanently retired and closed when a new facility was commissioned by the hospital in the south wing.

"Thirty years on, in 1999, intensive care finally gained acceptance and recognition as a specialty in its own right," writes Dr Anand in the Portrait of a Malaysian Anaesthetist. "An accredited training programme was subsequently established here in 2011. Mighty oaks from little acorns grow."

Leaning forward, Dr Anand emphasises: "And 54 years later, those services have grown. Things like major surgeries... what I do - heart and lung surgery - can't be done without ICUs. Liver surgeries, neurosurgery, transplantations... all those major advances couldn't have happened without ICUs."

A pause, and he muses: "If he didn't start the ICU, someone else would've eventually come along and done it. But he did it. And the hardest is always the first person doing it because you have no one to follow. You need to have the idea and the confidence to push it through!"

TRAILBLAZER

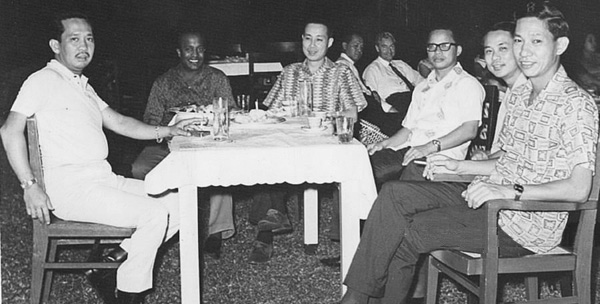

Johor Baru General Hospital pioneers (from left) Sachi, Dr Lim Kee Jin,

Dr Thomas Ng, Dr Ng Chuan Wai with then Johore Crown Prince

HRH Tunku Mahmud Iskandar

The dapper man with his trademark bowtie was a regular fixture around the hospital. Junior doctors saw him as a fair but firm mentor who emphasised on quality patient care. In seeking to provide patients with the best treatment possible, the skilful practitioner made several advances in his field.

One of his notable contributions was in the field of regional anaesthesia. Regional anaesthesia - then a relatively new concept - is the selective use of local drugs to numb or block sensations of pain from a large area of the human body, such as an arm, leg, chest or abdomen. This allows for surgery to be carried out on a region of the body with the patient being fully conscious, but pain-free.

Studies show that regional anaesthesia has fewer complications than general anaesthesia, and is less expensive. Recovery time is swifter and side effects are few, which can reduce the need for postoperative opioids.

Not content with simply following the familiar, well-trodden pathway of administering general anaesthesia, Dr Sachi pioneered and popularised contemporary techniques of central and peripheral nerve blockade in the country.

While this remains a poorly documented fact, Dr Anand's correspondence with Dr Alexius Delilkan, a long-serving highly published professor of anaesthesia at Universiti Malaya, revealed Dr Sachi's notable contributions in his field.

"Dr Sachi was the local pioneer of regional blockade anaesthesia," wrote Delilkan, "...and all who were trained by him in Johor Baru and Ipoh will never forget him as a clinical training academician".

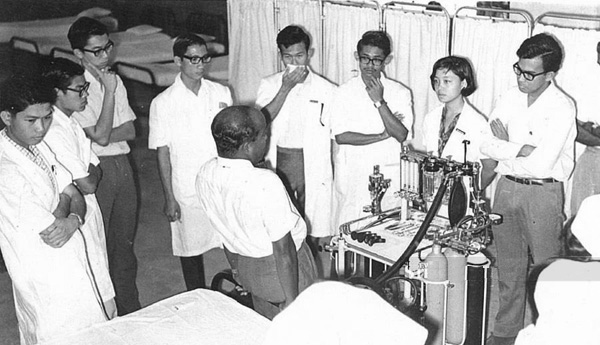

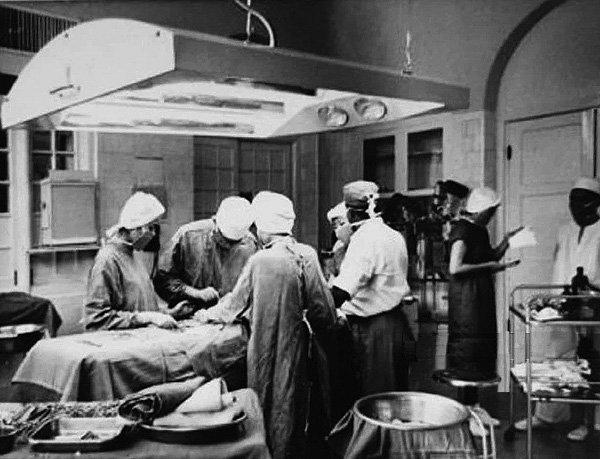

Postgraduate teaching of junior doctors and nurses on technical and clinical aspects

of anaesthesia, Johor Bahru General Hospital (early 1970s)

By the early 70s, Dr Sachi's anaesthesiology department at Johor Baru General Hospital had quickly gained a deserved reputation as an excellent training centre.

"My father saw the need for structured training. Back then, there were hardly any specialists, and training was carried out in a haphazard manner and very much at the whim of the bosses," shares Dr Anand, pointing out that his dad had a big role in formulating a structured training programme, and together with a few of his compatriots, had co-founded several medical institutions, including the Malaysian Society of Anaesthesiologists, KPJ Johor Specialist Hospital and the Faculty of Anaesthesiologists within the College of Surgeons Malaysia.

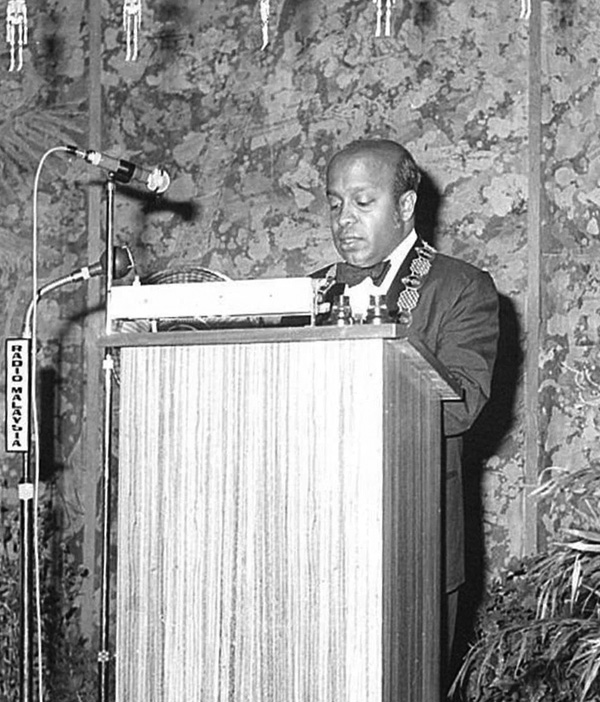

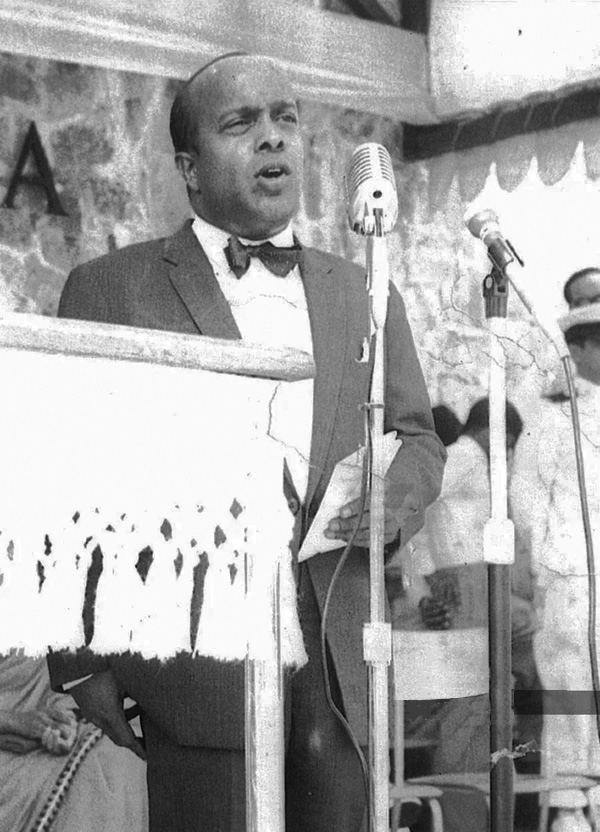

Presidential Malaysian Medical Association (MMA)

address by Dr Sachi (14th President) and the first

anaesthesiologist to lead the MMA. (March 1972)

His gift of teaching was proven when his department produced the highest number of junior doctors who started their anaesthetic careers there as medical officers and registrars. They would go on to successfully obtain their specialty fellowship in anaesthesiology.

Senior anaesthetist Dr Nirumal Kumar, who once worked in Dr Sachi's department in Johor Baru, recalls in Dr Anand's biography how the senior anaesthetist was always there to help when junior doctors ran into difficulties.

One morning at 6 am, Dr Nirumal couldn't intubate a patient. The staff nurse called Dr Sachi who came within 10 minutes. He helped intubate and stabilise the patient, told the junior doctor what do to at the end of the operation and left. The senior anaesthetist was back to work at 8 am sharp, looking as fresh as ever with a broad smile.

"His management style was 'leadership by example'," continued Dr Nirumal, adding: "He was very kind and caring to all his subordinates."

FATHER FIGURE

Dr Sachi was a natural leader and a visionary

whose contributions helped advance the medical

profession in this nation

While Portrait of a Malaysian Anaesthetist is jam-packed with medical history that can seem a little dry at times, Dr Anand's use of personal anecdotes (though few and far between) does capture a truth that seems to escape most physicians who pick up a pen: Being a doctor doesn't actually privilege one with access to the core of human experience; it's being human that does. Through history, stories and elegant writing, we learn about the good doctor and discover the person behind the career.

A kindly figure, immaculately attired with his paisley or polka-dot silk bowties (like a quintessential English gentleman) emerged with visionary ideas, mostly built on a genuine desire to help others.

"A lot of it may be too clinical," confesses Dr Anand, saying: "But I made a decision to document his professional work because papa had done so much for advancement of the medical profession here in Malaysia. It was only when I completed my studies and returned home after 18 years in Ireland and the UK that I began to discover the significance of my father's many contributions."

The book poignantly starts with Dr Sachi's untimely passing. He didn't survive an elective heart operation in London on May 1981, two weeks before Dr Anand's ninth birthday. He was 49.

"For my sister Sharmila and I, the day of his passing remains the saddest in our lives," writes Dr Anand. "His tragic, unexpected demise disrupted our lives unimaginably, leaving a chasm in our family that was never filled."

Dr Anand Sachithanandan

While his father's death shook him, transformed him, stripped the light from his gaze in the way death does, it was not a tragedy by any means. Dr Sachi passed on, successful in every important way, and surrounded by an adoring family. Despite losing his father at a young age, Dr Anand has some precious memories to hold on to.

"I remember him teaching me how to ride the bicycle. I remember the few occasions we went fishing and how we enjoyed my mother's delicious homemade chocolate milkshakes while playing chess and draughts (checkers). I remember him reading me bedtime stories and patiently patting me to sleep," recalls the 50-year-old wistfully. Those memories are faithfully captured in the book.

This isn't a book for everyone, he concedes. "Who's going to read this book?" he wonders aloud, before answering his own question thoughtfully: "He's not a world figure like Nelson Mandela. I'm writing about a very niche topic about an anaesthetist. It's most relevant to me in my mind to the people who knew him... knows me, who's interested in medical history, or past, current and future doctors who might find his story inspiring."

By the end of the book, we understand that while Dr Sachi's absence is devastating, shocking and total, Dr Anand will continue to find gifts his father left for him.

Dr Sachi's still there in his son's verve and curiosity, in his clear-eyed ability not just to write about his father, but also to love and care for people like his father did and walk in the same hallowed ground meant for doctors and physicians.

While he insists that the decision to take up medicine was purely his own and not influenced by his father's illustrious past, he would've loved to have had the time to glean some wisdom from him. "If he were alive today, I'd ask him what drove him to do what he did. What was he thinking?" he muses.

Dr Sachi and Dr Ng Chuan Wai maintained a healthy professional

and close personal friendship, epitomising how a dynamic

anaesthetist-surgeon relationship could benefit patients

(Johor Baru General Hospital, 1960s)

Dr Anand goes on to read an excerpt from a 91-year-old retired doctor and former colleague of his father, Dr Ng Chuan Wai.

"I've never forgotten the case of a patient who suffered from massive bleeding because of a duodenal ulcer and was in shock. Suitable blood for transfusion wasn't available and the senior ward sister had given up hope on him. I considered surgical intervention, but didn't think then that any anaesthetist would want to undertake the risk to anaesthetise him. Dr Sachi was consulted and he conceded that surgery was the only way to save the patient, urging me to carry out the emergency operation. He would administer the general anaesthetic.

"The surgical sister shook her head at our decision. While I was operating on the patient, I could see Dr Sachi moving here and there, drops of sweat visible on his forehead. Yet in the end, the operation was a success and the patient survived. The ward sister said it was quite a miracle. I said that the miracle was created by Dr Sachi because of his confidence, dedication and expertise.

"Then there was the case of my pregnant wife going through premature labour. The Johor Baru General Hospital had no facilities for premature baby care. My wife had to be rushed to Singapore maternity hospital, accompanied by her obstetrician in an ambulance. Dr Sachi insisted on coming along in case my wife needed emergency care on the way. He took me in his Jaguar and followed the ambulance all the way until my wife was admitted to the hospital. What a great friend he was!"

Dr Anand goes quiet again, smiling as he re-reads Dr Ng's message on his phone.

"This describes my father in a nutshell," he finally breaks the silence before concluding: "When I reached the age my father was when he passed away, it made me reflect on my own mortality. In learning about my father, I've discovered so much more about myself."

The V.I. Web Page

The V.I. Web Page