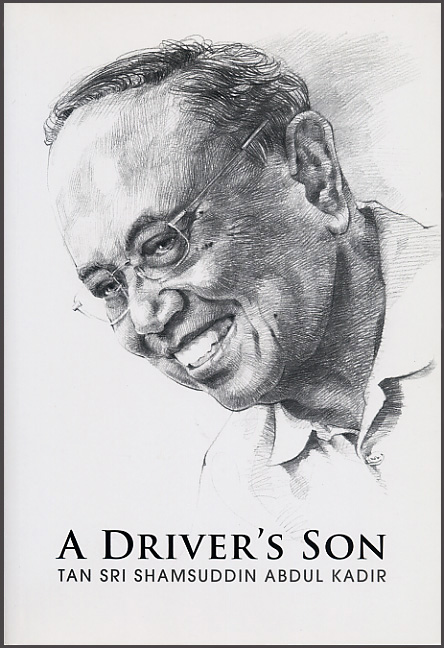

A Driver’s Son

Author: Tan Sri Shamsuddin Abdul Kadir

Publisher: MPH Group Publishing Sdn Bhd

Distributor: MPH Distributors Sdn Bhd

email: distributors@mph.com.my

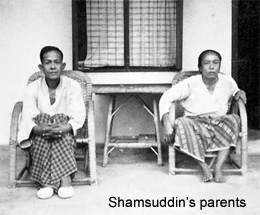

One of the most prominent businessmen in the country, Tan Sri Shamsuddin Abdul Kadir

reveals in his own words how he lived through poverty and navigated his way to the top

of the business hierarchy. A Driver’s Son documents more than just a legacy of business;

it’s also a story of family, humility, loss, gratitude and one man’s richness of spirit.

Shamsuddin at the V.I. (1954)

....Our return to the city reignited Bapak's hopes of getting me back into mainstream education, and after speaking with other drivers he learnt of a private English school that took in "overaged" students like me. The Mahatma Gandhi High School was a wooden house located on Jalan Yap Kwan Seng, not far from where the Australian High Commission is today. My teacher was a young girl named Janaky, whose husband Athi Nahappan went on to become the Deputy President of the Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC) of which she herself was a founding member.

Now that I was switching to the English medium, I effectively had to start from scratch, which meant I was admitted to Standard One at the age of 17. My teacher was not much older than I was and, needless to say, I towered over most of my classmates both in size and in age. But I was not the oldest one there — there was a Chinese boy from a wealthy family who was in his early 20s and who already had two children.

Despite the classes I had taken with Saberkas in Alor Star my English was still weak, but the classes I had in Standard One were generally based on fill-in-the-blank questions. Even if I didn't know the answer, I was in a better position to guess than my younger classmates. That meant I finished at the top of my class at the end of the first term, so the school double- promoted me to Standard Three. I came out tops again and was promoted to Standard Five during the third term. Things got a bit more difficult after that because the subjects now included Literature, but the fill-in-the-blank format kept my momentum going and I finished first once again.

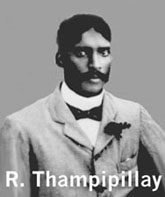

By this point we had a new headmaster, Mr R. Thampipillay,

who had been a teacher at the Victoria Institution. The VI was a

well-known and prestigious English school — a place I thought

of as far beyond my academic reach — but when Mr Pillay saw

my results at the end of the school year he said I should go

to a government school.

By this point we had a new headmaster, Mr R. Thampipillay,

who had been a teacher at the Victoria Institution. The VI was a

well-known and prestigious English school — a place I thought

of as far beyond my academic reach — but when Mr Pillay saw

my results at the end of the school year he said I should go

to a government school.

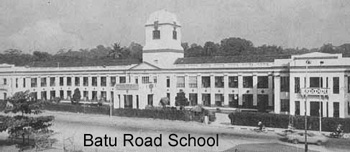

I hesitated at first, worried that my poor English skills would doom me in such an academically competitive environment, but the kindly Mr Pillay had so much confidence in me that I decided to give it a go. Classes at the VI started at Standard Five and although Mr Pillay believed I would be able to manage at the VI straightaway, I insisted that I would not be able to cope. We came up with a different strategy, which was to enrol me in Standard Four at the Batu Road School, another government school that was once a part of the VI but was now a feeder school. It was in a less affluent part of town, which hopefully meant that its standard of English would not be too high for me. Perhaps after a year in Batu Road, I would be ready for the VI.

I had worked hard on my English during my year at the Mahatma Gandhi High School, but I still found it difficult because I had little chance to practise outside of class. It was not as if I could practise with my father's boss, and watching English movies didn't help because I simply watched the action onscreen — especially the tembak sana sini, shoot-'em-up chaos of Westerns — and didn't listen to the dialogue. When a teacher asked me a question I had to think carefully before I answered in English, and I was shy about making a mistake in front of my much younger classmates because they would laugh at me whenever I did. I especially dreaded writing essays and I struggled with the grammar and my limited vocabulary.

When school re-opened in 1948, Bapak came

with me to meet Mr T.R. Abraham, the first local headmaster

of the Batu Road School. He took one look at me and said he

could not admit me because I was "much, much too old for

Standard Four." Most of the students in the class were 11 to

13 years old and I was already 18. Bapak pleaded my case but Mr

Abraham could not be persuaded to change his mind.

Standard Four." Most of the students in the class were 11 to

13 years old and I was already 18. Bapak pleaded my case but Mr

Abraham could not be persuaded to change his mind.

I think Bapak was more disappointed than I was. "Don't worry Din," he said as we left the school. "We'll try other government schools and I'm sure one of them will take you in." Neither of us said much the rest of the way home and I was already thinking that in the worst-case scenario, I could always go back to Mahatma Gandhi High School. Just as we were about to enter our quarters at the back of the residence, we heard Waring calling out to us. He asked if I had managed to get into Batu Road School, and I had to admit that I had been turned away for being too old. He did not seem surprised. Instead, he called out to his sister Margaret and asked her to take me back to the school the next day and make sure I was accepted.

"Shamsuddin, tomorrow you will go to the school with Margaret," Waring said. "And don't worry, they will take you in this time." Bapak drove us to the school the next day and stayed in the car as Margaret took me to meet Mr Abraham once again. After they had greeted each other, she matter-of-factly asked for me to be admitted to Standard Four.

"Certainly ma'am," Mr Abraham replied. "When can he start? If he wants to, he can start now."

There was no discussion about my age, no protest over my being too old. To be honest, I was annoyed that the treatment I was now getting was so different just because the same request had come from an orang puteh. Still, I was grateful to be getting the one thing I wanted so badly, so I didn't show how I felt and merely nodded. Margaret walked back to the car with Mr Abraham trotting a few paces behind her. Bapak opened the door for her, and as they drove off she stared straight ahead and didn't even notice Mr Abraham dutifully waving goodbye.

Mr Abraham admitted me into Standard Four D that very morning. I would have been happy to get into Standard Four E if it meant I still had a chance of getting into the Victoria Institution, which now didn't seem quite so out of reach. Still, the competition would be stiff — the VI only had 200 places on offer and there would be at least 400 contenders from feeder schools like the Batu Road and Pasar Road schools.

Despite being located in a poorer part of the city, the Batu Road School had the sons of royalty and politicians in its classes. I buckled down to my studies and, again, found that I had no problems aside from English and Literature. I didn't like the chore of memorising dates in History, but I managed. By my second term there I had been placed in Standard Four B, and that December I sat down with everyone else to take the entrance examination into Standard Five at the Victoria Institution.

The results came out in January and were posted on the notice board in the school hallway. I eased my way to the front of the crowd and started scanning the list from the bottom up. I was relieved to find that my name was not among the bottom 200 names. I anxiously moved my eyes up and my heart almost stopped when I couldn't find my name among the next batch of 100 students where I expected to be. It must have been my English, I thought, feeling miserable. I knew it would fail me. Still, where was my name?

Not expecting much, I skimmed over the first 100

names to see which of my friends had made it in... and at number

21, I saw it: Shamsuddin Abdul Kadir. I blinked, thinking there had

been a mistake. But there hadn't been one — not only had I made it

into the Victoria Institution, but I was being placed in Standard Five

A.

into the Victoria Institution, but I was being placed in Standard Five

A.

I rushed home feeling out of this world and broke the news to my parents. Bapak was ecstatic. All his efforts to make sure I earned a good education were starting to get results, but my getting into VI was beyond even his expectations. Over the next few days, whenever any of his friends asked him which school I had gotten into, he would grin from ear to ear when he shared the news. "Aku mahu hang pandai (I want you to be educated)," was what he said to me again and again, like a mantra. Waring, who by then was encouraging my efforts to converse with him in English, also congratulated me.

Mak remained typically restrained about her feelings, but she smiled and thanked God for my success. I flashed back to that day when she had given me the beating of my young life with an umbrella for trying to play truant, and it occurred to me that she was probably thinking at that very moment, "Ini pasal payong. (This is thanks to that umbrella.)"

I can't say she was completely wrong.

I stepped into the halls of the Victoria Institution in

January 1949 with a mixture of pride and apprehension. I'd essentially only

been back in the school system for two years and was still wrestling with

the complexities of the English language. Now that I'd made it into one of

the best schools in the country, I was anxious about whether I was going

to be able to do well enough to stay.

the best schools in the country, I was anxious about whether I was going

to be able to do well enough to stay.

At 19 years old I was also a lot older—and taller—than many of my classmates, most of whom were about 12. By then I had earned my nickname "Din Panjang" ("Tall Din") because when my friends and I rode around on our bicycles, I was the only one who needed to extend the seat all the way to the top. In all my classes I had to sit right at the back. Otherwise I would block the other boys' view, which put me at a disadvantage because my eyesight actually wasn't very good.

I also felt like a rusa masuk kampung (literally

"a deer in a village"), out of place and more than a little out of my depth

in an environment where even the youngest students spoke fluent, excellent

English. Most of them were from fairly privileged backgrounds and carried

themselves with a demeanour and confidence that I wasn't used to. But if I

initially felt intimidated by everything, excitement took over soon enough.

It was a big deal to be in the VI among the brightest children of the day,

and I was determined to work even harder than I had at the Batu Road School

in order to stand out.

themselves with a demeanour and confidence that I wasn't used to. But if I

initially felt intimidated by everything, excitement took over soon enough.

It was a big deal to be in the VI among the brightest children of the day,

and I was determined to work even harder than I had at the Batu Road School

in order to stand out.

The teachers gave us our booklist on the first day of school and I couldn't help but feel excited as I looked over the titles. It was a challenging list, filled with poetry and Shakespeare, all of which were foreign to me. My excitement quickly turned to apprehension once I managed to get copies of the books and tried reading a few pages. I cracked open A Midsummer Night's Dream and my heart sank a little when I realised that I simply couldn't understand what the lines were saying.

Students usually bought their books from other students or would go to Charles Grenier & Son Ltd bookshop near Ampang Road to buy them brand new or secondhand. I wanted all new ones, even though the secondhand ones already cost about three or four dollars each. Waring was kind enough to cover the cost. He also let me read the books in his library — I wasn't a great reader but I made sure to read the books that he pointed out to me, so that if he asked me about them I could answer his questions. One of the books he singled out was Jungle Green by Arthur Campbell, about British soldiers fighting Communist guerrillas in Malaya after the war. Another book was about explorer Thor Heyerdahl's 1947 voyage across the Pacific Ocean on the Kon-Tiki, a raft he made himself to prove how people in the past could travel vast distances across the seas. These were among the few books I read from cover to cover, which I knew made Waring happy.

One of the things that made going to the VI easier was that I had some of

my mates from the Batu Road School with me, but I made new friends as well.

One of the boys in my class was T. Ananda Krishnan, who was 12 or 13 at the

time. Ananda was very clever but he stammered, which made him the object of

bullying by other students. We became friends and hanging around me gave him

some protection because I was so tall — nobody dared to mess with us.

One of the things that made going to the VI easier was that I had some of

my mates from the Batu Road School with me, but I made new friends as well.

One of the boys in my class was T. Ananda Krishnan, who was 12 or 13 at the

time. Ananda was very clever but he stammered, which made him the object of

bullying by other students. We became friends and hanging around me gave him

some protection because I was so tall — nobody dared to mess with us.

In later years, Ananda's father wanted him to enter the science stream so he could become a doctor, but Ananda went into the arts stream instead. He told me later that his father was furious and had shouted at him, "If you want to be an artist then why do you need to go to university?" Everyone knows Ananda went on to become one of the most successful businessmen this country has ever seen, so I think it's safe to say that things turned out all right in the end. We remain friends to this day.

All of us were proud to be students at the VI, which was the only school in the country with a swimming pool and a science laboratory. The headmasters at VI were almost always mat salleh and they upheld a high level of academic rigour. There were four of them during my time in the VI before I sat for my School Certificate Examination in 1953. There was Mr Frederick Daniel, who wrote General Science for Tropical Schools; and he was followed by Mr E.M.F. Payne; Mr J.N. Davis; and then Mr G.P. Dartford, a historian who wrote A Short History of Malaya, a history textbook for Forms Four and Five. There were two others: Messrs A.H. Hill and A. Godman who were acting headmasters in between Payne and Davis.

My first headmaster, Mr Daniel, was a bachelor who lived

in the school quarters and spent much of the time in the laboratory. He was

an inspiration to many of us. We saw him as a great scientist and he was

known to apply his love for science to real-life situations, including the way

he ran the school. During one Friday assembly, for example — a thoroughly

formal affair for which we had to wear a tie, something I was never able to

master throughout my school days — Mr Daniel abruptly announced that

he had been testing samples of water from the swimming pool.

he ran the school. During one Friday assembly, for example — a thoroughly

formal affair for which we had to wear a tie, something I was never able to

master throughout my school days — Mr Daniel abruptly announced that

he had been testing samples of water from the swimming pool.

"Last week there was a high concentration of urine in the water," he said. "I will, therefore, close the swimming pool for two weeks to have it cleaned." Nobody wanted to see the pool closed any longer than it had to be, so there was an unspoken agreement after that never to be lazy about having to use the washroom while in the water. I hardly used the pool myself, being too lazy to do so.

Mr Daniel and his successors were also strict about upholding everyday discipline. Any rule-breaking — smoking or tardiness, for example was punished, usually in the most embarrassing way. Victoria Institution sat on top of Petaling Hill and was surrounded by a fence, which we had to paint if we committed any infraction. Whitewashing duties were carried out between noon and 1 p.m., not just because it was the hottest time of the day but also because we would then be put on display in front of pupils from other schools who came to VI to use the laboratory for their science classes. I ended up in the whitewashing gang once when I came late to school, and when it was the girl pupils on their way up the hill we turned the other way around so they couldn't see our faces.

Malay students had to wear a songkok every Friday but there were not that many of us. Each class had about 40 pupils and in Standard Five there were four other Malay boys besides me. The majority of the pupils were Chinese and Indian, and they must have been rich too as many of them were chauffeured to school in big cars. I knew where I stood: I was the son of a driver. But if I wanted to sit in a big car then I could take a ride with my father on the weekends in the only Rolls-Royce in Malaya, at a time when everybody else only had a Ford, Morris or Austin. So there was no need to feel envious.

My family moved with Waring to a new house on Stonor Drive,

but in 1951 Anglo-Oriental bought a plot of land in Damansara and began

constructing a new house for him. When it was completed the following

year, we followed him there. The house was named "Seronok" and then

"Sri Timah", but later became "Sri Perdana", the official residence of the

Prime Minister for many years.

year, we followed him there. The house was named "Seronok" and then

"Sri Timah", but later became "Sri Perdana", the official residence of the

Prime Minister for many years.

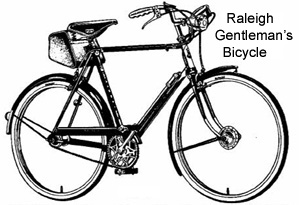

I was able to cycle to school on my Raleigh from where we were — the model was called the Gentleman's Bicycle, which I thought had a nice ring. Riding to school in the morning was a breeze because I could coast down the hill that Seronok sat on and it took me less than an hour to get to class. Riding home, however, was agony. It was uphill from the point where Muzium Negara is today all the way to the house. I was usually too tired and hungry to make it all the way on pedal power alone and would have to get off the bicycle and push it the rest of the way.

Fatigue and hunger weren't the only problems. One of the folk tales that Mak used to tell me as a boy was about the belief that tigers allowed themselves to be herded by birds known as kuang-kuit (the Pied Triller). Kuang-kuit was what their birdsong sounded like, hence the name. The birds would sit on the back of a tiger, feeding off lice and other insects. According to this folk belief, these birds would sing "kuang-kuit, kuang-kuit" loudly whenever they were far from tigers, but would do so softly when the big cats were nearby.

As it happened, there were lots of kuang-kuits

along the road I travelled to and from school every day. It was fine when

they sang at the top of their tiny lungs but whenever they got quieter I'd

get very jumpy... and would ready myself to shout and run if anything moved

out of the secondary jungle that fringed the road. It was not that bad

when I went home immediately after school ended, but I had extracurricular

activities on most days, which meant I could only start for home around

dusk. A tiger attack wasn't unheard of then — in Sept 1936 a tiger attacked

and killed a man in Pudu — although today the Malayan tiger has sadly almost

vanished from the wild.

out of the secondary jungle that fringed the road. It was not that bad

when I went home immediately after school ended, but I had extracurricular

activities on most days, which meant I could only start for home around

dusk. A tiger attack wasn't unheard of then — in Sept 1936 a tiger attacked

and killed a man in Pudu — although today the Malayan tiger has sadly almost

vanished from the wild.

Fleeing imaginary tigers aside, I studied hard and generally did well, always making it to the "A" class every year. Besides the occasional game of football I tried to use my extra time catching up on my lessons. If I found a class difficult, I tried to make sure I reviewed a lesson right after it was done to make sure I had understood it.

History continued to be a thorn in my side. I hated having to remember so many dates and names and I generally didn't like classes that involved having to memorise anything. To make matters worse, our history teacher Mr Rajadurai insisted on speaking in a tone that made all of us sleepy. One of the few things I remembered from the class was a lesson on the Black Hole of Calcutta, the 18th-century dungeon that was home to British prisoners of war. Sometimes when we couldn't remember what class we had next, we'd check our schedule, find out that it was History and then remind one another, "Oh, it's the Black Hole of Calcutta!" As usual I sat at the back of the room and often fell asleep, which would prompt Mr Rajadurai to say, "Can someone bring a mattress to the classroom?"

I enjoyed the science classes because they were logical, and having a scientist as our headmaster for some years and an actual laboratory to conduct experiments in piqued my interest in the subject further. Even those who were studying for entry into the universities had to practise in our lab, although they were only allowed to do so at night. I preferred chemistry and biology, and every week we went to the laboratory to dissect an animal and label its parts. We worked on rabbits and frogs, the latter of which were so plentiful near Waring's house that Bapak would catch some for me to bring to class.

English and Literature, however, remained my weakest subjects. I could tell that I was improving, especially as I now had so many opportunities to practise with others who spoke English well, but I still struggled to get high marks. I would spend an extra hour a day reading my books to help me improve but I admit I didn't enjoy it, especially if it was poetry or Shakespeare. We staged A Midsummer Night's Dream for two nights in Standard 7 and charged about 50 cents a ticket. It was an enormous success — I was involved in setting up the stage and such — and as a result it was probably the only Shakespearean play I ever really understood.

It didn't help that I didn't get along with my English and

Literature teacher, Mr Ganga Singh, who was also our class teacher when I

was in Standard Eight. The fact that we always got the headmaster's shield

for being the cleanest class in VI is some indication of how Mr Singh ran

things (he even made us polish all the door hinges). Most of the boys

would get a mark of 6/10 or 7/10 for their English essays. This was no

surprise as the boys spoke nothing but English in school and at home. Mr

Singh regularly gave me a 2/10, which was an endless source of frustration

for me. He also often directed his criticisms at the Malay boys in class as we

were all older than everybody else. You didn't talk back to your teacher in

those days and I never complained about it to Bapak either, knowing full

well he would just tell me not to be lazy and to work harder.

was in Standard Eight. The fact that we always got the headmaster's shield

for being the cleanest class in VI is some indication of how Mr Singh ran

things (he even made us polish all the door hinges). Most of the boys

would get a mark of 6/10 or 7/10 for their English essays. This was no

surprise as the boys spoke nothing but English in school and at home. Mr

Singh regularly gave me a 2/10, which was an endless source of frustration

for me. He also often directed his criticisms at the Malay boys in class as we

were all older than everybody else. You didn't talk back to your teacher in

those days and I never complained about it to Bapak either, knowing full

well he would just tell me not to be lazy and to work harder.

I found out that the other boys who did well also attended Mr Singh's after-school tuition classes at his house, but I couldn't afford them. Bapak's salary was $37 then, and Mr Singh charged $15 a month for the privilege of taking his extra classes. On several occasions, he would give me 2.5/10 for my essay. Whenever this happened he would ask me to stay back after class and ask, "Shamsuddin, your essay today is much better. Was it your own work?" I knew it was his way of getting me to sign up for his tuition class, but I think even if we had been able to afford it I would have refused.

Failing to get me to sign on, Mr Singh would show me official circulars that were regularly sent to schools to recruit students to fill vacancies in government departments. He always caught me as I was going out for recess or when the class was almost empty. "Shamsuddin, come here a moment," he would say. "This is a circular from the Malay Regiment announcing their new intake. All you need is a Standard Seven qualification. It says here that during training you will receive $272 a month and you will graduate as a Second Lieutenant, with pips on your shoulders. Wah Style!" Another time, he said I could join the police force as a probationary inspector. But he always pointed to my age: "You are nearly 22 while the others in your class are just 15 or 16," he said. "You should be working by now instead of studying." In my later years at the VI, Mr Singh persisted in trying to get me to leave school to join either the police or army.

It was tempting, not least because earning a decent salary would mean Bapak could stop working. He could rest and I could take my turn taking care of the family. My parents had sacrificed so much for me and I had always known that caring for them in later years would be my responsibility, and mine alone. There were also times when I believed Mr Singh when he would berate me and say that I would never get anywhere in life. But I was determined to complete my studies and at least get my School Certificate, and I knew Bapak wanted me to go even further. After everything my parents had done for me, I felt responsible for their hopes and did not want to disappoint them. So I persevered and said no.

But what would I do with my life? I wanted to get a job and initially thought that even as a government clerk, I could earn something like $90 a month, still more than my father. The circulars that Mr Singh kept dangling in front of me reminded me of when my family had first moved to KL when I was five. I had watched fresh police recruits in their smart uniforms on the parade grounds and I had yearned to be one of them. Mr Singh certainly thought I belonged in their ranks. The idea had not completely lost its lustre, but I began thinking about the possibility of going further with my education and becoming something else.

My fascination with the sciences made me briefly consider becoming a doctor. People said studying to be a doctor would be difficult, but the different parts of the body don't ever change. I thought, however, that I was too old to study to be a doctor as I would only graduate in my early 30s. I also recalled the times I'd been in hospitals visiting friends and seeing doctors running different tests and trying different medicines — it seemed like guesswork and I wanted to do something more exact.

Engineering is exact. You cannot guess at the results and you cannot bluff your way to them. When engineers bluff, things collapse. The precision of engineering — the inescapable exactness of this discipline — appealed to me. As I progressed through my years of study at the VI and came closer to the time when I would sit for the School Certificate Examination, I started thinking about becoming an engineer. At some point during our many moves around the city, we had lived near the first Malay to become an electrical engineer, Raja Zainal Raja Sulaiman. He was an engineer with the National Electricity Board and I sometimes spotted him driving a sports car, looking very smart. I told myself that if I were an engineer, I could look like that too.

Shamsuddin (back row, second from right) at a restaurant with his VI teachers and classmates

Several years after I graduated from the Victoria Institution, I returned to the school with some fellow alumni to visit during one of its Sports Days. I had joined Telecoms by then after earning my qualifications as an engineer. Mr Singh was still teaching there and came over when he spotted us to ask what we were each doing with ourselves. My friend Husin was the Assistant State Secretary in Selangor, while my other mates Tajuddin and Shamsir were a government dentist over at Sultan Street and a chartered accountant respectively.

Mr Singh nodded wisely at each bit of news then turned to me.

"Shamsuddin, what do you do?"

"I'm at Telecoms."

"Oh, as a technician, eh?"

"Yes sir," I replied. "But I also have a room with a sign that says 'Assistant Controller.'"

"Oh," he said. "That is an engineer's post."

"Yes sir. I am a qualified engineer."

There were many other things I wanted to say to Mr Singh to remind him of how he had tried to discourage any ambitions I might have had while in school, but he chose that moment to walk away. My friends just looked at me and one of them said, "Din, you managed to knock him out."

Yes, I finally got my TKO. That moment, however, was still many years in the making.

...By this time I had a firm group of friends: there was Ali Ibrahim, the son of a police sergeant who lived in the barracks in the Police Depot on Gurney Road and who went on to become the Director of Education; a chap named Tajuddin who became a dentist; and Wan Yahya Pawan Teh, whose father was a magistrate. But I was closest to Wan Yahya's brother, Wan Mahmood, whom I had first met in Standard Six and who was two years ahead of me. The brothers spoke excellent English; in fact, they all did, so being in this circle of friends helped me to improve my English, giving me a safe space in which I could practise speaking the language without feeling embarrassed about my mistakes.

Wan Mahmood was a student activist and a member of a

group called the Malay Students Literary Society. It not only promoted

nationalism but worked to help "overgrown" students like myself who

had missed out on years of schooling because of the war. Although this

was how we first met. Wan Mahmood and I became friends beyond the

Society's activities. He and his brother would correct any mistakes

I made and even helped me by going over my English essays before I

handed them to the teacher. I began to see the results of their help too

- even though I failed my mid-terms in English that year, I still managed

to get a personal best of 40/100.

had missed out on years of schooling because of the war. Although this

was how we first met. Wan Mahmood and I became friends beyond the

Society's activities. He and his brother would correct any mistakes

I made and even helped me by going over my English essays before I

handed them to the teacher. I began to see the results of their help too

- even though I failed my mid-terms in English that year, I still managed

to get a personal best of 40/100.

Wan Mahmood and I became very close despite the difference in our backgrounds. I was the son of a driver and he was the son of a magistrate, which was an important thing to be at the time, but he was always there for me. It didn't matter to him that I was a nobody, and for some reason he chose my company over other boys whose fathers also occupied elevated positions, like District Officers and Chief Ministers. He encouraged me in my schoolwork and boosted my spirits when I was worried about my exams. He was a real joker in school and was known for pulling pranks like nailing our friends' desk lids shut. I didn't know it then, but Wan Mahmood was to become more than a friend in the ensuing years, and he remains someone I trust and value today.

By the time I reached Standard Nine my English had improved to a point where I could speak and write in the language with more comfort than I could have ever hoped for. But was it enough for me to pass the School Certificate Examination at the end of the year? After all those years of study, would I be able to live up to my parents' hopes for me? If I earned a Grade One, then I would have the chance to continue with my studies, perhaps with a government scholarship. If you had money then the results didn't matter as you could get a lowly Grade Three and still go on to study. But for me, getting a good result would help to shape my future.

I was lucky that my class teacher that year was Mr Lai Nyen

Foo. Mr Lai owned eight horses, which meant he had money, which in turn

meant he didn't need to work. He was at the VI because he loved to teach and

he was good at it too, always encouraging his students to push themselves.

"I don't have to teach you if you don't want to learn," he used to say.

"You don't have to lift heavy things—just sit down and learn." He never

discriminated against me because of my age and always rewarded me with

words of encouragement whenever I worked hard.

he was good at it too, always encouraging his students to push themselves.

"I don't have to teach you if you don't want to learn," he used to say.

"You don't have to lift heavy things—just sit down and learn." He never

discriminated against me because of my age and always rewarded me with

words of encouragement whenever I worked hard.

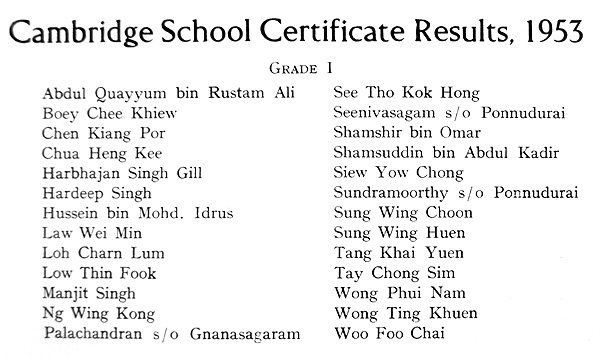

We sat for the School Certificate Examination that December. In January, based on my mid-term examination results, I qualified to enter Form Six and entered the science stream. All of us, however, were anxiously waiting for our SCE results, which were due to come out in March. I decided to hedge my bets and so applied to join the army. If I was accepted I would be trained in Port Dickson. I also applied to the Telecommunications Department and the Perak Malay Higher Study Scholarship, which was only for those born in the state. I had no idea how well I had done in the exams so I told myself it was wise to keep these options open, just in case.

The big day finally came. All of us who had sat for the

exams were instructed to assemble in the school hall, where we were greeted

by the sight of our teachers sitting in a row facing us. We took our seats

and remained quiet as Mr Payne, then the school principal, stepped up to

the front and began announcing the names of students in alphabetical order

and the grades they had obtained.

and remained quiet as Mr Payne, then the school principal, stepped up to

the front and began announcing the names of students in alphabetical order

and the grades they had obtained.

The first Malay name to be called was Hussin Idrus, who earned a Grade One. The next two Malay names were Mokhtar and Shamsir, who earned a Grade Two and a Grade One respectively. I held my breath—the next Malay name would be mine. Mr Payne kept going, a steady roll call of names and grades, and I suddenly realised he was now reading out names starting with "T". Had I missed my name being called? I was certain I hadn't. My name had been missed out altogether and in my mind that could only mean one thing: I had failed.

Even though I had taken care to keep my other options open, there had been a small part of me that thought I wouldn't need them. It was a big blow to realise that I hadn't passed the exam. I could feel my face start to flush and, not wanting to face the humiliation of being pitied by my classmates, I quietly got up and walked out of the hall.

How could I have failed? I had revised my lessons endlessly and done my best. Surely I could have at least passed with a Grade Three? I decided that I must have failed English, a mandatory pass subject. It had always been my Achilles' heel and even now, after years of practice and extra help from friends like Wan Mahmood, I had still failed to conquer it. The topic for the exam composition had been, "Describe the most memorable event in your life," and I had chosen to describe the day Japanese soldiers had pulled me out of school to send me off either into forced labour at the Death Railway or into the fight in New Guinea. It had been a harrowing experience and I had written without hesitation, recalling the event in great detail. Clearly, it had not been enough.

I cycled home slowly and could not hide my sorrow or my tears when I broke the bad news to my parents. Mak tried to console me by saying I could try to take the exam again at the end of the year, while Bapak said that even the boys who didn't go to school could get a job. I would find something, he assured me, perhaps with the police or the Malay Regiment.

Despite their encouraging words, I could sense their disappointment. I barely touched my dinner that night. Sleep was also a long time coming and I think I eventually dozed off because I felt emotionally worn out.

The next morning, I stood red-eyed and depressed in the compound of Seronok, trying to decide what to do next when I spotted a cyclist struggling up the slope to the house. When he reached our gate I recognised the rider as Ramlan, the school's office boy. Uncertain what he was doing at the house, I walked up to him and noticed that he was sweating and breathing hard. "Oi, Shamsuddin," he gasped. "Look at me, lah. I'm sweating and out of breath, all because of you. Mr Lai wants to see you."

"What does he want with me? I have failed."

"He told me he wants to see you now. He said you haven't failed."

Without any further explanation Ramlan turned his bicycle around and started down the slope, looking back to throw me one last grin. "Come quickly!" he yelled, and with a wave of his right hand, he disappeared from view.

Excited but somewhat confused, I went to our quarters to get my bicycle and rode down the slope after him. Once I reached the school I went straight to the teachers' common room to look for Mr Lai. He spotted me before I saw him and he motioned me to come over. "Why did you walk out of the hall before all the results were announced?" he asked.

"My name was not called, sir, so I saw no point in staying."

"You should have checked with me before you left. You passed, Shamsuddin."

I stared at Mr Lai, perplexed. "Yes sir, Ramlan told me. But sir, this is no time for jokes."

"No Shamsuddin, you passed," he insisted.

As Mr Lai stared earnestly into my face, waiting for the news to dawn on me, I could feel life being restored to my limbs.

"Grade Two, sir?" I asked, trying hard not to show my excitement. Knowing I had actually passed was an enormous blessing after the shock of the previous day, but dare I hope that I had done even better than a Grade Three?

Mr Lai beamed as he told me: "Grade One."I felt like I was being lifted off my feet, I was so happy. It was a long way to come from the depths of my misery the day before. Thank God, thank God, I kept thinking to myself. But I wanted to be assured.

"Show me the results, sir," I said. Mr Lai passed me a slip of paper and there it was, in black and white, the words "Grade One" next to my name. I had earned three As: in Malay, Chemistry and Biology. And I had obtained a C in English, which was good enough for me. I felt so relieved that I didn't care I was now weeping in front of Mr Lai. In a way, my tears were an expression of my gratitude for all the trust he had placed in me.

"You silly boy! You shouldn't have left the hall yesterday," he said. Mr Lai had been so confident that I had passed that after the assembly, he went straight to the school office to double-check the results. Sure enough, a mistake had been made. In those days the results were sent to the respective schools on microfiche. The school clerks would use a magnifying glass to read the results and copy them onto a list, which was then used to make the big announcement in the school assembly. My name had simply been missed out by accident during the preparation of the list, and Mr Lai found it quickly enough after checking the microfiche himself.

So I had passed! With a Grade One! I headed out to celebrate with my friends, many of whom had gotten a Grade Two or Grade Three. We cycled to the Kampung Baru Sunday market and ordered mee rebus and ice kacang. We chatted, we boasted, we spun tales. At that moment, the future seemed close enough to touch and bright enough to dream about. We stayed at the market until the late afternoon, and then I headed home once again to share the very different news with my parents.

Yes!

The V.I. Web Page

The V.I. Web Page